This article was originally published by The Long Now Foundation and is republished here under a CC BY-NC-ND 4.0 international license.

In April 02023, The White House proposed major regulatory changes with huge implications for how the federal government considers the environmental impacts of new projects. The news barely made a blip in headlines.

The proposed changes concern two arcane documents called “Circular A-4” and “Circular A-94” that set recommendations for how federal agencies conduct cost-benefit analyses for social projects. Specifically, the US Office of Management and Budget (OMB) proposed lowering the discount rate from between 3% and 7% to 1.7%.

If you’re still there, let me explain.

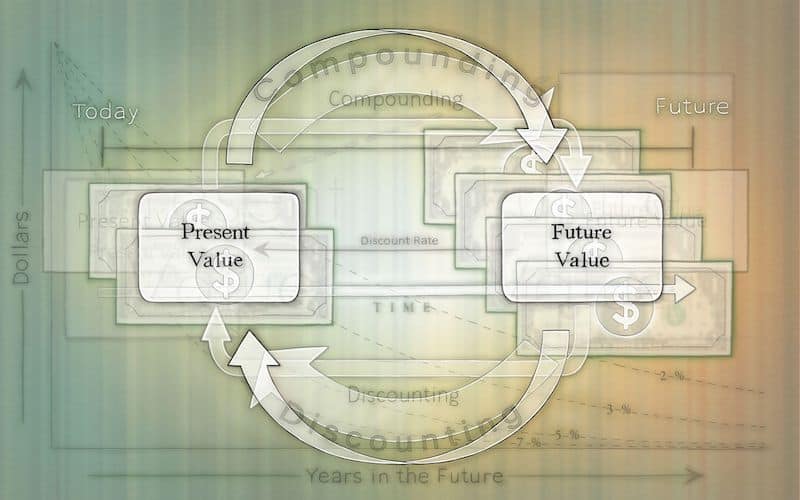

Unless you’re a policy wonk or a certain kind of federal contractor, you can be forgiven for not knowing what the discount rate is. The discount rate or the “social discount rate” is a modeling rate for discounting the cost of future impacts in terms of present value, and it’s often used in the cost-benefit analysis of social projects that will have a delayed effect. Not to be confused with the discount rate set by the US Federal Reserve, which sets the interest rate charged to banks by the Fed, the social discount rate is mostly used by various government agencies in project planning.

The higher the discount rate, the less we value future impacts in the present. By contrast, a lower discount rate means we place a higher value on future impacts. This often gets applied to financial figures, but it can also be applied to benefits like lives saved.

The social cost of carbon is a good example. This metric seeks to quantify the harm caused by carbon emissions in terms of dollars. In 02021, the federal government used a 3% discount rate to arrive at a cost of $51 dollars per metric ton of CO2, in 02020 dollars. That cost rises every five years, so at a 3% discount rate, the cost in 02020 dollars would go up to $56 in 02025, $62 in 02030, and so on.

Critics of a low-cost calculation of carbon praised the proposed decrease to a 1.7% discount rate — a sharp departure from the 7% discount rate employed by the Trump administration. This set the social cost of carbon as low as $1 — something made possible by ignoring climate impacts on other countries — and made it much easier for fossil fuel projects to get approval. But in the proposed changes published earlier this year, the Biden administration recommends lowering the discount rate even further for projects with more long-term effects.

If all of this still sounds obscure and confusing, it might help to consider an example from the 02020 science fiction novel The Ministry for the Future by Kim Stanley Robinson.

As far as sci-fi writers go, Kim Stanley Robinson stands out for a few reasons: he’s widely regarded as one of the best science fiction authors alive today, he writes extensively about the climate and ecological crisis, and he likes to do so through the language of political economy, throwing around terms like “carbon quantitative easing” amid the standard science fiction themes of his work. If ever there were a sci-fi writer who had his characters talk about the discount rate, it would be him.

The book follows Mary Murphy, an Irish woman who becomes the leader of a fictional Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) office called the Ministry for the Future in the year 02025. The Ministry for the Future is tasked with advocating for the rights of future people who will suffer from the climate change previous generations caused. In Chapter 32, Mary asks Dick, a minor character, what his team is doing to improve economics for future people. Dick tells Mary they’re studying some changes India has made to its discount rate, saying:

[India’s] idea is to shape the discount rate like a bell curve, with the present always at the top of the bell. So from that position, the discount rate is nearly nothing for the next seven generations, then it shifts higher at a steepening rate. Although they’re also modeling the reverse of that, in which you have a high discount rate, but only for a few generations, after which it goes to zero.

That proposal is, of course, fictional. Yet it raises important questions about our own world — and our own economy. Why do we discount the future so heavily? What does that mean for climate change? What are some different ways we might imagine the discount rate to help fight climate change?

…

Picture this: a ship sails in one direction on an endless ocean. When it stops at various ports along the way, different groups of passengers board and disembark, but the passengers have limited control over where the ship goes next, and therefore, who comes aboard. Like all ships, this one requires regular maintenance and repairs to stay seaworthy, but each group of passengers has finite time and resources it can devote to repairs before passing them off to the next group. How should current passengers spend their time and resources on repairs to be the most fair to future passengers?

This analogy from philosopher Nicholas Vrousalis provides an introduction to the subject of intergenerational equity, or intergenerational justice. Intergenerational justice has ancient roots, with one example being the Seventh Generation Principle found in the Potawatomi, Ojibwe, and Haudenosaunee Native American cultures.

In the Western tradition, the political philosopher John Rawls provides much of the foundation for today’s discussions. Rawls’ idea of a “just savings principle” suggests people alive today should “save” enough to leave future people just institutions and the ability to enjoy the same benefits previous generations left those of us alive today. It’s sort of like political philosophy’s equivalent to the Golden Rule: live for future people the way you wish people in the past would have lived for you.

Intergenerational justice concerns itself with determining the responsibility current generations have to other generations. These could be people who haven’t been born yet, but it also includes seniors and children. The social discount rate plays an important part in such discussions, and opinions differ on what that role should look like. One of the strongest arguments comes from economist Tyler Cowen and the late moral philosopher Derek Parfit.

In their influential paper “Against the Social Discount Rate,” Parfit and Cowen make the case for setting the social discount rate at 0%, effectively getting rid of it. The basic reasoning goes like this: the problems of future people will be just as real as ours are today when they arrive. How can we morally make an argument for valuing them less just because they don’t exist yet?

Parfit and Cowen’s paper considers a number of arguments against a 0% discount rate, one of the most common of which says we should discount effects on future generations because they’ll be better off than us. Sure, Parfit and Cowen say, some future people will probably be better off than us, but some future people will also be worse off than us. That alone is a good enough reason to ditch the social discount rate.

But The Ministry for the Future takes up another argument against a 0% discount rate, which I will call “The Argument from Infinity.” In Chapter 32, Dick tells Mary:

See, if you rate all future humans as having equal value to us alive now, they become a kind of infinity, whereas we’re a finite. If we don’t go extinct, there will eventually have been quite a lot of humans — I’ve read eight hundred billion, or even several quadrillion — it depends on how long you think we’ll go on before going extinct or evolving into something else…If we were working for [future generations] as well as ourselves, then really we should be doing everything for them. Every good project we can think of would be rated as infinitely good, thus equal to all the other good projects.

Paradoxically, by valuing future people less, we can perhaps be better ancestors and set them up to better cope with their problems. But in an interview, Cowen told me that he doesn’t find the Argument from Infinity convincing.

“The world’s going to end,” Cowen said. “And I don’t mean in a billion years, you know. How long do species last? You could look up the number, but it’s just not that long.”

But what about the remaining issue Robinson brings up about all good projects being infinitely good? Wouldn’t this demand that we sacrifice everything for the sake of future generations?

Parfit and Cowen again reject this in their paper, not because we should be able to demand that the current generation sacrifice everything but because a social discount rate doesn’t actually address this issue. It could lead us to, for instance, forgo preventing a major catastrophe in the future even if it would cost the same as preventing a minor catastrophe tomorrow.

Cowen expanded on this in our interview. “If you just think, ‘What can we actually do for the distant future?’ there’s very little we can do to help those people. The main thing we can do…is to leave them good institutions — a good constitution, good social norms, whatever you might put under that rubric. And that we should be very careful to make sure we do.”

Cowen’s argument for a 0% discount rate, then, doesn’t obligate us to take on every moonshot that could save lives in 03400 or 10320. Instead, by leaving a solid foundation of options for future generations, we can grant them the same wealth of choices prior generations granted us.

…

There’s one last argument in favor of non-zero discount rates worth considering here: The Argument from Special Relations. According to this argument, we all naturally use a kind of discount rate when we prioritize people who are related to us over others. For instance, most people will make sacrifices for their children before they will for strangers. Parfit and Cowen acknowledge this, saying, “Such claims might support a new kind of discount rate. We would be discounting here not for time itself, but for degrees of kinship.”

Earlier, I mentioned the Seventh Generation Principle from various Native American cultures as an example of an intergenerational equity concept. Though this idea is far from new itself, it can help us piece together the “new kind of discount rate” Parfit and Cowen began to sketch out in their work. By listening to indigenous community leaders putting the Seventh Generation Principle into action today, it’s possible to build a roadmap for our societies as we race to reorient our ways of living to be more harmonious within planetary boundaries.

Journalist, professor, author, and Bad River Band of Lake Superior Ojibwe citizen Patty Loew writes about this philosophy in her book Seventh Generation Earth Ethics: Native Voices of Wisconsin. In an interview, Loew explained the Seventh Generation Principle.

“Seventh Generation, I think, is a broad notion of stewardship,” she said. “Seventh Generation thinking obligates us in this generation to make decisions that we think are in the best interests of generations seven into the future…And when you think about the really wicked problems that human beings face…I think those kinds of problems really require us to think with more vision.”

Loew said this philosophy is interpreted differently across Native communities, and even within communities. Some communities, she said, interpret Seventh Generation to include three generations forward and three generations back in addition to the present generation.

“The other thing that’s kind of interesting about Seventh Generation thinking is that it also means you look back with gratitude,” Loew said. “So the decisions that my great-great-great grandfather made when he signed two of the three Ojibwe session treaties, he was thinking about my generation and understanding that the land that he was being coerced into giving up — the reservation — was not going to be large enough to sustain the generations that came after. So we were one of the few tribes that insisted on the right to hunt, fish, and gather on the land that we were giving up.”

Of course, the Seventh Generation Principle is part of a larger worldview that stands in stark contrast to modern ways of thinking in terms of commodities. Loew cited examples of Seventh Generation thinking during our interview, especially the sustainable logging and forestry management practices of the Menominee Tribe in Wisconsin. Over the past 160 years, Menominee Tribal Enterprises has been sustainably logging the Menominee forest, resulting in more trees in the forest than it had before their logging operations began. Loew attributed this to a different way of thinking about the forest: instead of viewing it as a commodity, the Menominee see it as a relative.

“Right now, we have more volume of wood in our forests than we did 100 years ago…even though we’ve cut the forest, the volume, over four times since then,” Jonathan Wilber, president of Menominee Tribal Enterprises, said in an interview with Insight on Business. “We do not just manage our forest for the trees. We manage the forest for the animals, the streams, the species of plants that are out there. This forest has to be managed for the long haul.”

In The Ministry for the Future, there’s a part of the exchange between Mary and Dick where Mary asks how the discount rate is calculated. Dick’s clever reply: “Out of a hat.” This is one major critique of the social discount rate: no matter who ends up determining it, it’s somewhat arbitrary. Some might say the same when considering ways to incorporate Seventh Generation thinking into our economic systems. After all, isn’t seven also an arbitrary number?

But fixating on the exact number misses the point. As Cowen noted in our interview, we don’t know what people living 300 years from now will need. Instead, we should focus on leaving them good institutions, which, I would argue, should include a healthy environment. Thinking in terms of special relations — both in terms of relationships across generations and of other beings as relatives — can help us sort out the details of that broader goal. When we are bound in a system of reciprocity, not return on investment, we will be closer to being the kind of ancestors future people need.

Leave a Reply