Stories for Earth relies on contributions from our listeners and readers to produce high quality, in-depth content. If you buy something using the links on our website, we may earn a small commission, at no extra cost to you. For more information, see our Affiliate Disclosure.

Gun Island and The Great Derangement by Amitav Ghosh could not be more appropriate books for discussion on this podcast—they’re both about the role stories play in fighting the climate emergency! In this episode, I summarize and analyze Gun Island, using The Great Derangement as a critical framework. If that sounds a little academic, don’t worry. Ghosh is a very accessible writer, and I found his ideas brilliant yet easy to understand.

Audio only

Never miss an episode

Subscribe wherever you enjoy podcasts:

Jump to

About the creator

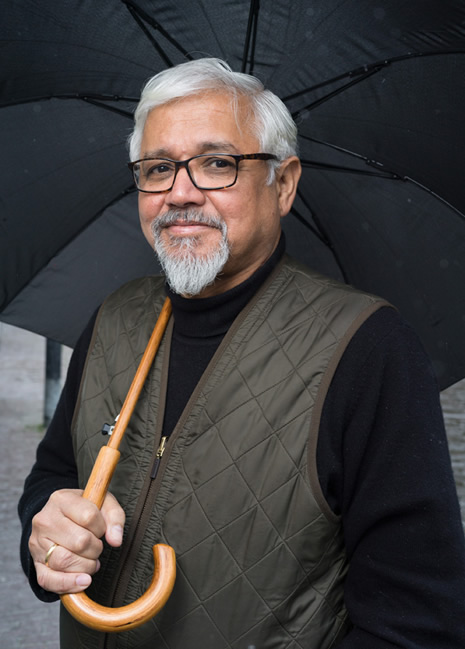

Born in Calcutta, India, Amitav Ghosh is the author of The Great Derangement, Gun Island, and multiple other works of fiction and nonfiction. His 2017 nonfiction book The Great Derangement: Climate Change and the Unthinkable won the inaugural Utah Award for the Environmental Humanities in 2018, and his 2008 novel Sea of Poppies was shortlisted for the Man Booker Prize. His latest book, Jungle Nama, was released in 2021. Amitav Ghosh divides his time between Brooklyn, Kolkata, and Goa.

Official website: http://www.amitavghosh.com/

On Goodreads: https://www.goodreads.com/author/show/3369.Amitav_Ghosh

On Twitter: @GhoshAmitav

On Instagram: @amitav_ghosh1

Transcript

One of the first times I can remember eating lobster, I was 10 years old. My family wasn’t one to splurge on expensive groceries, so fried shrimp was about the only seafood we ate growing up. But the lobster and other seafood we got that summer were relatively inexpensive. A man driving a refrigerated van through our neighborhood rang our doorbell, and my mother bought a lot of seafood from him. He had just come up to Atlanta from New Orleans after Hurricane Katrina hit, and he was trying to sell everything before it went bad.

Though I was too young to fully understand it at the time, a lot of people like that man came up after Katrina, some of them driving even further than the eight hours it takes to get to Atlanta from New Orleans. Some of them went back, but a lot of them didn’t—as much as 40 percent, according to Salon. The hurricane itself did a lot of damage, but the flooding caused the worst of it. Many of the levees that held back the Gulf of Mexico burst with the storm surge, which was as high as 30 feet, or 9 meters, in some places.

Also read: “Beasts of the Southern Wild,” Hurricane Katrina, and Climate Change

When all was said and done, up to 80 percent of New Orleans was underwater. And even though the mayor had issued a mandatory evacuation order the day before the hurricane hit, thousands of people, consisting mostly of the city’s poorest residents, were homeless, and over 1,800 people had died, including people in Alabama, Mississippi, and Georgia. At $125 billion in damages, Hurricane Katrina was the most expensive storm in US history, tied only recently with Hurricane Harvey in 2017. Even now, almost 16 years later, the city is still recovering, especially the hardest-hit neighborhoods like St. Bernard Parish and the Ninth Ward.

As for the people who hadn’t returned to New Orleans two years after the storm? Many of them still haven’t returned, and they have no intention of doing so. Some people have called this the largest mass-exodus of people in the US after the Dust Bowl in the 1930s. But this isn’t a uniquely American phenomenon. Around the world, there is a refugee crisis of people fleeing conflict zones to seek a better life for themselves and their families. And it is directly tied to the climate crisis.

“Gun Island” plot summary and analysis

Immigration and climate change are major themes in the novel I recently finished reading, Gun Island by Amitav Ghosh. Published in 2019 by Farrar, Straus, and Giroux, Gun Island is the story of Dinanath, or Deen, Datta, a rare book dealer from Kolkata, India who splits his time between Brooklyn and Kolkata. And just so you know—yes, many spoilers lie ahead.

Deen is a strict realist; he has no belief in the metaphysical, and he thinks the stories in the antique books he sells are nothing more than just stories. But after a chance encounter with a distant relative in India, Deen sets off on a wild goose chase, if somewhat reluctantly, to crack the legend of the Gun Merchant, an ancient myth in the flavor of the Odyssey that tells of a man’s travels as he tries to escape the goddess of snakes, Manasa Devi. Deen’s quest to understand the legend of the Gun Merchant takes him all over the world, leading him to cross paths with an interesting cast of characters in rather synchronous ways. The novel is good by itself, but I found it made for a much more enriching experience to read it alongside Amitav Ghosh’s nonfiction book, The Great Derangement. More on that to come.

The legend of the Gun Merchant

Deen travels first to a shrine on a remote island in the Sundarbans, an Indian national park of lush mangrove forests in the delta region between India and Bangladesh. There, he meets Tipu, a street-smart and tech-savvy teenager who guides Deen to the shrine in the Sundarbans. Tipu, Deen learns, is a smuggler who helps people from India and Bangladesh immigrate illegally to other countries where work and money are easier to come by. This is where we first encounter climate refugees in the novel, as Tipu says on pages 87 and 88:

In these parts, there’s a whole bunch of dirt-poor, illiterate people scratching out a living by fishing or farming or going into the jungle to collect bamboo and honey. Or at least that’s what they used to do. But now the fish catch is down, the land’s turning salty, and you can’t go into the jungle without bribing the forest guards. On top of that every other year you get hit by a storm that blows everything to pieces. So what are people supposed to do? What would anyone do?

Gun Island, pp. 87-88

When they arrive at the shrine, Deen and Tipu meet up with Rafi, a peasant boy from nearby who knows about the significance of the shrine in the legend of the Gun Merchant from stories he grew up hearing from his grandfather. But while Rafi is showing Deen around the shrine, he’s attacked by a cobra, forcing the three to flee by boat so they can get Rafi to a hospital. On their way, the venom causes Rafi to start convulsing and having disturbing hallucinations about someone who’s chasing him, and Tipu tries to provide comfort by staying with him below deck.

Deen in the US

Once they arrive at the hospital and Rafi stabilizes, Deen has to leave abruptly to catch his flight to New York. Not liking the cold, Deen winters in Kolkata and spends the rest of the year in Brooklyn. But it would seem whatever haunted Rafi after being bit by the snake has also latched onto Deen. He becomes paranoid and hardly leaves his apartment until his old friend Cinta invites him to an academic conference in Los Angeles. Cinta is one of Deen’s oldest friends, and she’s currently researching the role of Venice, Italy in the ancient spice trade. Unlike Deen, Cinta is somewhat of a mystic, believing she’s seen the ghost of her dead daughter and scolding Deen for dismissing the legend of the Gun Merchant as some silly folk tale.

After much indecision from Deen, he eventually decides to meet Cinta in LA, though he’s paranoid about the city’s encroaching wildfires and haunted by strange visions of the snake on his trip, leading to an embarrassing and scary incident at the airport. Deen manages to make it to the conference, which is mostly full of stuffy, old-fashioned academics who scoff when a younger researcher gives a presentation on literature and climate change.

However, Cinta is sympathetic to the young scholar, talking to Deen later about why he’s wrong to think the legend of the Gun Merchant is just a story. Cinta says on page 176:

At that time people recognized that stories could tap into dimensions that were beyond the ordinary, beyond the human even. They knew that only through stories was it possible to enter the most inward mysteries of our existence where nothing that is really important can be proven to exist—like love, or loyalty, or even the faculty that makes us turn around when we feel the gaze of a stranger or an animal. Only through stories can invisible or inarticulate or silent beings speak to us; it is they who allow the past to reach out to us.

Gun Island, pg. 176

This is part of a larger theme in the book—the role of literature in addressing the climate crisis—which matches Ghosh’s argument in The Great Derangement that we should look to literary traditions further in the past than modern, realist literature if we’re to write the kind of literature climate change demands of us.

Eventually, Deen’s fears about the California wildfires materialize, and the conference has to be evacuated because the fires get too close. This seems almost too perfectly-timed to be merely coincidence, given the discussions that were just going on at the conference. But Deen insists on believing that the events are meaningless—nothing more than bad timing—heading back to the hotel and flying back to Brooklyn.

Venice

A good while later, Deen leaves New York again, this time bound for Venice, Italy to stay at Cinta’s apartment while she’s out of town and to clear his head from the persistent snake visions he keeps having. While in Venice, Deen discovers that many of the people responsible for creating an authentic Venetian experience (cooking the pizzas, steering the gondolas) are actually Bengali migrant workers. In fact, he almost hears as many people speaking Bangla as he does Italian. Notably, he hears the Madaripur dialect of Bangla, which is where Deen’s family was originally from before the region was split after West Bengal became part of India and Bangladesh became an independent country.

This has a double effect on Deen: on one hand, it’s a point of pride for him to think of Bangla becoming an international language like English or German, but on the other hand, he realizes that more people are leaving West Bengal and Bangladesh than he perhaps previously thought. The latter really hits home when he runs into Tipu, who’s working multiple jobs as an illegal migrant worker. At first, Tipu is evasive—he doesn’t want to see or talk to Deen, but after some prodding, Deen eventually gets Tipu to talk to him, who tells him that he and Rafi left India together but got separated along the way while crossing over into Turkey from Iran.

Also read: “Weather” by Jenny Offill

Tipu hasn’t seen Rafi since then, but he has good reason to believe he might be crossing the Mediterranean on a small blue boat from north Africa along with other migrants and refugees. However, they don’t have a way of confirming this, so Deen sets off to learn more about the migrant community in Venice, trying to get someone to agree to an interview for a friend who’s making a documentary about the refugee crisis.

Around this time, Cinta returns to Venice, and in the coming days she shows Deen around to some of the most meaningful places in Venice to her. In doing so, the two have conversations about uncanny events and experiences they’ve had that can be connected to climate change. Deen, especially, keeps coming back to a spider that scared him while staying in Cinta’s apartment. It was a brown recluse spider, a species that recently migrated north to Italy due to rising temperatures in Africa. This prompts an important dialogue in which Cinta asserts that the world is “possessed” since individuals no longer have to assert their presence in the world but are shuffled through life by machine-like systems.

She says on page 296:

“Just look around you, caro [dear].” There was a touch of weariness in her voice now. “Everybody knows what must be done if the world is to continue to be a liveable place, if our homes are not to be invaded by the sea, or by creatures like that spider. Everybody knows…and yet we are powerless, even the most powerful among us. We go about our daily business through habit, as though we were in the grip of forces that have overwhelmed our will; we see shocking and monstrous things happening all around us and we avert our eyes; we surrender ourselves willingly to whatever it is that has us in its power.”

Gun Island, pg. 296

After an accident that sends Cinta to the hospital one night as she’s showing Deen around Venice, news breaks of the little blue boat from north Africa that Tipu was talking about. Deen’s documentary filmmaker friend, Gisa, wants to go on a boat to meet it, and she asks Deen to go with her. Cinta tags along, too, despite hardly being able to walk, and Deen takes Tipu so he can see if Rafi is indeed on the blue boat.

In search of Rafi

It takes a couple of days to sail out to the part of the Mediterranean where the boat is supposed to appear, but when they get there, they’re also met by the Italian Navy and private ships from far-right protesters and pro-immigration counter-protestors. The rightwing protestors have flags and do chants like, “Close borders now!” and “L’Italia agli Italiani!” or “Italy for Italians!” This was the name of an actual coalition of neo-fascist Italian political parties in 2018, one of whose leaders was the Italian politician Roberto Fiore, who self-identifies as a fascist. Deen joins in with the crew of his boat and the counter-protestors to shout, “NO to xenophobia! NO to hate!” A short while later, on page 379, he reflects on what he’s witnessing:

I saw now why the angry young men on the boats around us were so afraid of that derelict refugee boat: that tiny vessel represented the upending of a centuries-old project that had been essential to the shaping of Europe. Beginning with the early days of chattel slavery, the European imperial powers had launched upon the greatest and most cruel experiment in planetary remaking that history has ever known: in the service of commerce they had transported people between continents on an almost unimaginable scale, ultimately changing the demographic profile of the entire planet. But even as they were repopulating other continents they had always tried to preserve the whiteness of their own metropolitan territories in Europe.

Gun Island, pg. 379

This is one of the strongest commentaries in the novel on the relationship between colonialism, imperialism, and the climate crisis. Something seems to click for Deen in this scene, as he realizes that hundreds of years of European colonialism is the root cause of the climate crisis. And now that Europeans are facing the consequences of the enormous ways in which they changed the planet, a significant number of them don’t want to accept it.

Despite the calls for them to be turned away, the little blue boat carrying Rafi and the others makes it through the blockade. Just as the boat is coming into Italian waters, a multitude of different sea creatures—some of them quite rare—surge to the surface of the sea and charge right between the Italian battleship and the little blue boat. The weather also starts going haywire, with waterspouts appearing all around them, making for a spectacular display of nature’s power. Gradually, the animals all pass through, the weather calms down, and the admiral of the Italian battleship makes an announcement over loudspeakers that the little blue boat is safe and that the Italian Navy will guide them to shore.

These final, almost supernatural scenes of the novel fulfill the legend of the Gun Merchant. After he makes it to the same boat as Deen and Tipu, Rafi looks back at where he came from in astonishment and remarks, “It’s just as it says in the story—the creatures of the sky and sea rising up…”

Later, the Italian media is buzzing about the admiral’s decision to let the little blue boat pass—a decision to disobey orders from the Italian prime minister directing the admiral to prevent the boat from landing in Italy. Earlier in the novel, the prime minister said it would take a miracle for the blue boat to land, to which the admiral calmly replied at a press conference, “What the Minister has said, in public, was that only in the event of a miracle would these refugees be allowed into Italy…And I believe that what we witnessed today was indeed a miracle.”

The ending of “Gun Island,” explained

In the last several paragraphs of the book, Deen reflects on everything that’s happened to him in the span of a few months. He remembers one of the places Cinta took him to when she was showing him around Venice: Santa Maria della Salute, or the Salute, an old Roman Catholic church built after a severe outbreak of bubonic plague in 1630 that was dedicated to the Virgin Mary to thank her for restoring health, or salute, to Venice. Inside the basilica, an image of the Virgin Mary stands at the altar that bears the inscription Unde Origo Inde Salus, which translates to “Whence our Origin Hence our Salvation.”

Thinking about how the little blue boat was seemingly saved by the fulfillment of an ancient prophecy is significant to Deen. On page 389 he writes:

In that instant of clarity I heard again that familiar voice in my ear, repeating those words from La Salute—Unde Origo Inde Salus—“From the beginning salvation comes,” and I understood what she [Cinta] had been trying to tell me that day: that the possibility of our deliverance lies not in the future but in the past, in a mystery beyond memory.

Gun Island, pg. 389

It seems that in the final moments of the novel, Deen finally comes around to Cinta’s belief that the legend of the Gun Merchant wasn’t just a story, but an important and meaningful message that remains relevant today.

“Gun Island” as a response to “The Great Derangement”

On the surface, Gun Island may seem like a fun, fast-paced adventure story, but there’s a lot going on beneath the surface that’s easy to miss on a first read. To really get the most out of this novel, it’s helpful to read it critically using Amitav Ghosh’s nonfiction book The Great Derangement as a guiding framework.

Published in 2017 by the University of Chicago Press, The Great Derangement is based on a series of four lectures Amitav Ghosh gave at the University of Chicago for the Berlin Family Lectures. In the book, Ghosh explores the hesitancy of literary fiction to address climate change and questions why books that do address climate change are often disregarded or looked down upon by the literati as pulp or science fiction.

The role of literature in the climate crisis

Ghosh begins by discussing what is considered serious, literary fiction and how it came to be, arguing that modernist, individualistic, so-called realist fiction is anything but realistic. He points to stories outside of the modernist and realist movements as more accurate depictions of real life—stories that weren’t as self-aware, usually more collectivist and which featured abrupt and dramatic events that modernists might dismiss as fantastical.

Ghosh argues that the modernist tradition of telling stories that focus on one main character with lots of interiority are actually shortsighted, quoting Charlotte Brontë writing to a critic, “…is not the real experience of each individual very limited?”

Ghosh is also critical of the way in which modernist and realist literature depicts nature, sharing passages from the realist novels Madame Bovary from the French literary virtuoso Gustave Flaubert and Rajmohan’s Wife by Bankim Chandra Chatterjee, a 19th century Bengali writer who aimed to incorporate Western realism into Indian literature.

Realism gave rise to what Ghosh calls filler, a storytelling device where “…instead of being told about what happened we learn about what was observed.” He turns to the Italian literary historian Franco Moretti to explain why this trend may have taken hold. On page 19 of The Great Derangement, Ghosh quotes Moretti saying, “…fillers are an attempt at rationalizing the novelistic universe: turning it into a world of few surprises, fewer adventures, and no miracles at all.”

Flaubert and Chatterjee, Ghosh says, wrote about nature as something very tame and gradual. If your perception of nature comes largely from reading books like Madame Bovary, for instance, you might be shocked to see a real-life event like a tornado or a tsunami, two natural phenomena that are very spontaneous and violent.

You might also balk at events like the eruption of Mount Tambora in 1815, which many scientists believe caused a volcanic winter responsible for the “Year Without a Summer” in 1816. This event was so sudden and dramatic that it actually caused a drop in global temperatures, giving Europe and other parts of the world record-setting cold temperatures and causing famines due to crop failure. In fact, some historians credit this as the inspiration for Mary Shelley’s groundbreaking novel Frankenstein, an ironically realist novel itself despite its fantastical elements.

Looking to the past for inspiration

What Ghosh is getting at is this: nature is not tame or neat, so why do we write about it like it is? If you take a fiction writing class, some of the first pieces of advice your teacher will give you are to drive the plot by asking yourself what the main character wants and to be wary about using sudden, unexpected events.

Your protagonist is walking down the sidewalk one day when suddenly they’re hit by a car that jumped the curb. Too abrupt—take it out. Your protagonist is at a party when suddenly the deck collapses, sending everyone to the emergency room. This isn’t driven by any character’s will or desire—consider using a different device for developing the plot.

Also read: “The Overstory” by Richard Powers with Lovis Geier: Summary & Analysis

There is an age-old argument about whether or not fiction should accurately depict real life, but senseless, random events happen all the time. It seems silly to reduce them to a minimum or to eradicate them altogether from our novels. In the age of the climate and ecological crisis, it seems even sillier. Sudden, unexpected, and unforeseen events are on the rise as global temperatures increase, a phenomenon that Hunter Lovins of the Rocky Mountain Institute termed “global weirding.”

To be clear, not all modern fiction is like this. There’s a whole subgenre of speculative fiction called ecological weird fiction, and works of magical realism are replete with bizarre and sudden events. Take, for example, the gypsy merchant Melquíades dying and coming back to life multiple times in One-Hundred Years of Solitude by Gabriel García Márquez, or ancient beasts called Aurochs causing a massive storm in the film Beasts of the Southern Wild. Ghosh acknowledges magical realism, but he also grapples with its role in addressing climate change. At a time when the fossil fuel industry spends exorbitant amounts of money on climate change disinformation campaigns, Ghosh worries about the implications of telling climate change stories through the lens of magical realism.

Rather, Ghosh suggests we should look to older traditions of storytelling, like the legend of the Gun Merchant in Gun Island, for inspiration on how to write about climate change. As we’ve seen already, this is one of the central themes of the book: the argument between Deen and Cinta over whether or not older stories remain relevant in the modern world. Remember, Deen is a dealer of rare, antique books, but he sees them as commodities, more of collector’s items than living stories. But by the end of the novel after Deen has watched the legend of the Gun Merchant play out in real life, he realizes ancient storytellers were more intelligent and wise than he previously gave them credit for.

Empire and climate change

We often point to carbon emissions as the root cause of the climate crisis. And while carbon emissions do cause the greenhouse effect that leads to global warming, Amitav Ghosh would argue the roots of the climate crisis run deeper.

A brief history of colonial India

In the second section of The Great Derangement, Ghosh gives us a history lesson, going back to the beginning of British colonial rule in India in the 17th century when the British monarchy granted the East India Company permission to establish a trading post in what was then the Mughal Empire.

Over the next couple hundred years, the East India Company came to dominate the Indian subcontinent despite conflicts with other European colonial powers like the French and the Dutch. The Mughal Empire gradually collapsed in addition to the other kingdoms of India, and the East India Company built a private army to exploit India before the British crown had to eventually intervene and assume power in the 19th century. The British remained in control of India until 1947, two years after the end of World War II, at which time the colony was split into the independent countries of India and Pakistan.

This span of over 300 years was a dark time for India, with cruel, violent treatment from the private armies of the East India Company and massive famines that killed tens of millions of people. Europeans were originally drawn to India to establish a spice trade, but shortly after the Industrial Revolution came around in the late 18th century, another commodity from the East started to see a spike in demand: oil. Oil was plentiful in Burma (Myanmar), and Ghosh notes that after the Second Anglo-Burmese War of 1852-53, oil became big business in the region.

Many oil fields in present-day Myanmar were controlled by King Mindon Min, the king of Burma, until the British invaded in 1885. This paved the way for the Burmah Oil Company of Scotland to basically establish a monopoly on oil production in the Indian subcontinent, which it maintained until the American oil company Standard Oil set up Burmese operations in the early 20th century. The Burmah Oil Company was eventually acquired by British Petroleum (BP), shifting operations away from India after the discovery of oil in the Middle East.

This might seem like a lot of history, but it’s an important backstory for understanding how we got to where we are today. As Ghosh takes care to note in The Great Derangement, if it weren’t for British invasion, the beginnings of the modern fossil fuel industry might have originated in South Asia. Under colonialism, the British and other European colonial powers repressed technological and economic development in the territories they occupied, effectively hindering them from developing fossil fuel economies until much later.

In recent years, China and India have made major contributions to the climate crisis, contributing 28 and seven percent of global CO2 emissions, respectively. But Ghosh argues that if it weren’t for European colonialism, we might have seen this spike earlier. To be clear, the United States of America and the 28 countries of the European Union are responsible for the lion’s share of historical emissions between 1751 and 2017. According to Our World In Data, the US and the EU make up 25 and 22 percent of historical emissions, respectively. Compared to historical emissions from China (12.7 percent) and India (three percent), it’s clear that modern emissions stats don’t show the full picture. In fact, China’s emissions didn’t even eclipse American emissions until 2005, according to Climate Watch.

Ghosh is also quick to point out that there were outspoken leaders in many Asian countries who opposed industrialization. On page 111, Ghosh quotes some of Mahatma Gandhi’s writing from 1928: “God forbid that India should ever take to industrialism after the manner of the West. If an entire nation of 300 millions [sic] took to similar economic exploitation, it would strip the world bare like locusts.”

And yet, we’re in a far worse position today. In 2019, the population of the United States was 330 million people. In the same year, India’s population was 1.3 billion people. I don’t bring this up to say that overpopulation is the cause of the climate crisis but to emphasize that even nearly a hundred years ago, people knew the high-consumption, carbon-intensive cultures of industrialized countries were unsustainable. Now we’re reaping the consequences of failing to heed that wisdom, and, tragically, countries like India, Bangladesh, Indonesia, and the Philippines—some of the countries least responsible for global warming—will suffer the worst effects.

Reaping the consequences of colonialism

So what does any of this have to do with the novel Gun Island? First of all, Gun Island is a story about many modern issues, but you could make a pretty convincing argument that above all else, it’s a story about climate refugees—people from colonized countries fleeing the effects of a climate crisis caused by colonialism. We see this most clearly with characters like Rafi and Tipu, and especially at the end of the book with the little blue boat crossing the Mediterranean.

The legend of the Gun Merchant itself might also be interpreted as the story of a climate refugee. The legend tells the story of a merchant on the run from the goddess of snakes because he refuses to be her devotee. The goddess is relentless, and she chases him everywhere, sending natural disasters to make him change his ways. Ghosh has commented on the legend as well, saying in an NPR interview that it was written as an allegorical tale to represent the dichotomy between nature and the “profit motive.”

Reading the book with an awareness of colonialism and climate refugees makes this pretty obvious, but Ghosh makes a clear statement about this theme on pages 363-64 through a Bengali immigrant Deen meets named Palash:

But everyone has a dream, don’t they, and what is a dream but a fantasy? Think of all the people who come to see Venice: what’s brought them there but a fantasy? They think they’ve travelled to the heart of Italy, to a place where they’ll experience Italian history and eat authentic Italian food. Do they know that all of this is made possible by people like me? That it is we who are cooking their food and washing their plates and making their beds? Do they understand that no Italian does that kind of work any more? That it’s we who are fuelling this fantasy even as it consumes us? And why not? Every human being has a right to a fantasy, don’t they? It is one of the most important human rights—it is what makes us different from animals. Haven’t you seen how every time you look at your phone, or a TV screen, there is always an ad telling you that you should do whatever you want; that you should chase your dream; that ‘impossible is nothing’—‘Just do it!’ What else do these messages mean but that you should try to live your dream?

Gun Island, pp. 363-64

Put another way, Ghosh writes on page 92 of The Great Derangement:

It is Asia, then, that has torn the mask from the phantom that lured it onto the stage of the Great Derangement, but only to recoil in horror at its own handiwork; its shock is such that it dare not even name what it has beheld—for having entered this stage, it is trapped, like everyone else. All it can say to the chorus that is waiting to receive it is “But you promised…and we believed you!”

The Great Derangement, pg. 92

People in wealthy western countries enjoy a very high standard of living. Of course, there are massive inequalities—especially in the US—but many of us still live in relative comfort thanks to machines like cars, dishwashers, washing machines and dryers, refrigerators, and air conditioners. We like to believe that we have these things because we worked hard or persevered or followed our dreams, but the truth is we have such massive material wealth because we used colonialist practices to exploit countries like India, Bangladesh, and Myanmar for their natural resources.

At least in the United States, there’s a strong tendency to believe that colonialism is a thing of the past, that it’s a relic of the 19th century. Even though the United Kingdom retained India as the so-called “crown jewel” colony until 1947, many westerners still think of colonialism as something distant. But a practice like colonialism that lasted for hundreds of years and had such profoundly disastrous effects on its victims won’t just go away in less than a century. The refugee crisis we’re experiencing today in Europe and in North America is a consequence of colonialism, and it stands to get worse as more vulnerable countries begin feeling the effects of climate change.

Also read: “Infest The Rats’ Nest” by King Gizzard & The Lizard Wizard

This is further intensified by the culture of consumerism that Western countries have fostered that has now spread around the globe. Palash is right—we are constantly told to follow our dreams and to buy things that will supposedly make our lives better. But consumption of this kind is totally unsustainable.

Every year, Earth Overshoot Day marks the date when the world has collectively consumed more ecological resources than the Earth can regenerate in a calendar year, and the date keeps coming earlier and earlier. In 2020, Earth Overshoot Day was August 22nd, but this date also varies by country. In 2021, the United States hit Earth Overshoot Day on March 14th. By contrast, Indonesia will hit Earth Overshoot Day on December 18th. Even a country like Switzerland—which is considered green by so-called developed countries—will hit Earth Overshoot Day on May 11th this year. If everyone on Earth lived like the Swiss, we would need 2.79 planet Earths to remain within sustainable ecological limits. And remember, that’s by good standards compared to most other Western countries!

The fact of the matter is that humanity as a whole cannot continue living the way we’re living if we want to have a habitable planet by the end of the century. Living truly sustainably will require massive changes to our fundamental systems of society. This is not only a scientific, economic, sociological, and political challenge, but also a challenge of our imagination and creativity.

Imagining a better future

Last year, I did an episode about Ishmael by Daniel Quinn, and it remains one of the most impactful books I’ve ever read. Ishmael tells the story of a gorilla named Ishmael who has learned to talk to humans. He manages to escape from the circus where he’s being held, and he puts an ad in the newspaper telling anyone who’s interested in saving the world should come see him. At least one man—the narrator—takes him up on the offer, and the rest of the book is a Socratic dialogue between the narrator and Ishmael.

Also read: “Ishmael” by Daniel Quinn, Climate Change, and Moving Beyond a Vision of Doom

Ishmael explains that the core delusion of humanity that has caused the climate and ecological crisis is that we are somehow above nature rather than part of nature. Or, as Lizzie from the novel Weather by Jenny Offill puts it, “The core delusion is that I am here and you are there.” This is what Ishmael calls our mythology, and he proposes that the key to saving ourselves lies in recognizing this mythology and creating a new mythology that works for all life on Earth.

The problem is that people don’t realize the trap they’ve fallen into. Just like Ishmael had to realize he was in a cage before he could be free, we have to do the same. In Gun Island, Deen and Cinta come to a similar conclusion when Cinta tells Deen that the world is possessed. On page 380 when Deen goes to meet Rafi on the little blue boat, he makes a profound statement: “The world had changed too much, too fast; the systems that were in control now did not obey any human master; they followed their own imperatives, inscrutable as demons.” So how do we free ourselves from this demonic possession?

Up until recently, a dominant narrative in the environmental movement has been one of shame. If only more people would take public transit instead of buying SUVs, if only more people would stop eating meat, if only more people would stop using single-use plastics. But rather than continuing with these pleas, Ishmael suggests a different approach. Near the end of the book he says, “…people need more than to be scolded, more than to be made to feel stupid and guilty. They need more than a vision of doom. They need a vision of the world and of themselves that inspires them.”

Amitav Ghosh echoes this sentiment in The Great Derangement, saying on pages 128-129:

And to imagine other forms of human existence is exactly the challenge that is posed by the climate crisis: for if there is any one thing that global warming has made perfectly clear it is that to think about the world only as it is amounts to a formula for collective suicide. We need, rather, to envision what it might be.

The Great Derangement, pp. 128-29

This is where I think stories come into play, but not just any stories. The stories that will help save us from ourselves must challenge the fundamental ways in which we unconsciously view the world. They must stoke our imagination and creativity and inspire us. I think these stories can come in many, many different forms, but for Ghosh, at least in Gun Island, some of these stories were already written a long time ago when humans lived in closer connection to the Earth.

Also read: “Pacific Edge” by Kim Stanley Robinson: A Future Mythology

On page 389 of Gun Island, Deen reflects on everything that has happened to him, saying:

In that instant of clarity I heard again that familiar voice in my ear, repeating those words from La Salute — Unde Origo Inde Salus — “From the beginning salvation comes,” and I understood what she had been trying to tell me that day: that the possibility of our deliverance lies not in the future but in the past, in a mystery beyond memory.

Gun Island, pg. 389

Thus, Deen—a dealer of rare, antique books—realizes the answer he’s been searching for has been there the whole time.

What you can do to help

So now you’re probably wondering, what do we do with these stories that inspire us? How do we follow their example to change the way we live? Daniel Quinn says we need to act as if they’re already true. Of course, this is easier said than done, but there are some small actions we can take today that can turn into big actions over time.

If you were moved by Gun Island and you want to help with some of the issues raised in the novel, I would suggest looking into ways to get involved with the following organizations:

International Rescue Committee

Website: https://www.rescue.org/

Charity Navigator Rating: 86.92/100 (source)

The International Rescue Committee responds to the world’s worst humanitarian crises and helps people whose lives and livelihoods are shattered by conflict and disaster to survive, recover and gain control of their future. In more than 40 countries and over 20 U.S. cities, our dedicated teams provide clean water, shelter, health care, education and empowerment support to refugees and displaced people.

“The IRC’s impact at a glance,” https://www.rescue.org/page/ircs-impact-glance

Doctors Without Borders

Website: https://www.doctorswithoutborders.org/

Charity Navigator Rating: 92.25/100 (source)

Doctors Without Borders/Médecins Sans Frontières (MSF) is the world’s leading independent international medical relief organization, implementing and managing medical projects in close to 72 countries worldwide and as a worldwide movement of 33 offices and associations.

Our work focuses on emergency medical and humanitarian relief. We are guided by the principles of independence, neutrality and impartiality, as described in the MSF Charter. We implement our medical programs in areas where no health or sanitary systems exist, or where health structures are overwhelmed by the needs of populations.

“About us,” https://www.linkedin.com/company/medecins-sans-frontieres-msf

Amnesty International

Website: https://www.amnesty.org/en/

Charity Navigator Rating: 89.39/100 (source)

Amnesty International is a global movement of more than 10 million people who take injustice personally. We are campaigning for a world where human rights are enjoyed by all.

“Who We Are,” https://www.amnesty.org/en/who-we-are/

Chintan

Website: https://www.chintan-india.org/

Charity Navigator Rating: Not available

Our mission is to ensure consumption is more responsible and less burdensome on the planet and the poor. We strive to reduce waste and unsustainable consumption and enable better management of that waste which is generated. We also focus on fighting air pollution through making science and policy more accessible to everyone, thus creating public vigilance and action. In all our work, vulnerable populations—the poor, the marginalized, children and women—will remain the sharpest on our radar.

“Our Mission,” https://www.chintan-india.org/who-we-are

Greenpeace India

Website: https://www.greenpeace.org/india/en/

Charity Navigator Rating: 84.95/100 (Note: score for Greenpeace Fund in the US, source)

We believe optimism is a form of courage. We believe that a billion acts of courage can spark a brighter tomorrow. To that end we model courage, we champion courage, we share stories of courageous acts by our supporters and allies, we invite people out of their comfort zones to take courageous action with us, individually in their daily lives, and in community with others who share our commitment to a better world. A green and peaceful future is our quest. The heroes of our story are all of us who believe that better world is not only within reach, but being built today.

“Our Vision,” https://www.greenpeace.org/india/en/about/

It may sound corny, but building a better world starts right now. These are only five charitable organizations working to help with issues like the refugee and climate crisis, so I’d encourage you to do some research of your own as well to find organizations or causes that resonate with you.

Recommendations

Book: The Hungry Tide by Amitav Ghosh

→ Buy USED on Better World Books from $3.98

→ Buy NEW on Bookshop from $15.63

→ Find at your local library

Article: “Amitav Ghosh: ‘The World Of Fact Is Outrunning The World Of Fiction’” by Ari Shapiro in NPR

Book: This Changes Everything: Capitalism vs. The Climate by Naomi Klein

→ Buy USED on Better World Books from $6.30

→ Buy NEW on Bookshop from $17.47

→ Find at your local library