Stories for Earth relies on contributions from our listeners and readers to produce high quality, in-depth content. If you buy something using the links on our website, we may earn a small commission, at no extra cost to you. For more information, see our Affiliate Disclosure.

If epic fiction is your thing, you will love The Overstory by Richard Powers. Published in 2018 by W. W. Norton, The Overstory is an ambitious environmental fable of nine main characters (yes, nine) that explores our relationship with nature, the psychology of why we’re so bad at acting on climate change, our perception of time, the meaning of hope, and so much more. Garnering praise from legends like Bill McKibben, Barbara Kingsolver, Michael Pollan, and Ann Patchett, it’s easy to see why this novel was shortlisted for the Man Booker Prize in 2018 and won the Pulitzer Prize for Fiction in 2019.

→ Buy USED on Better World Books from $10.78 (affiliate)

→ Buy NEW on Bookshop from $17.43 (affiliate)

→ Find at your local library

Truth be told, I finished reading this book late last year, but I never could find the right words when I sat down to write about it. My new friend Lovis Geier had similar feelings when we connected earlier this year, so we decided to tackle this behemoth together. The product is a departure from the typical episode format when I discuss a work of literature, but I don’t think I could have done it any other way for The Overstory. Be sure to check out Lovis’ YouTube channel Ecofictology, and join us on the Rewilding our Stories Discord server to participate in engaging conversations about eco fiction and cli-fi.

Audio only

Audio and video

Become a Patreon of Ecofictology for the full 2-hour video discussion!

Never miss an episode

Subscribe wherever you enjoy podcasts:

Jump to

- About Richard Powers

-

Transcript

- Nicholas Hoel (Watchman) character analysis

- Olivia Vandergriff (Maidenhair) character analysis

- Mimi Ma (Mulberry) character analysis

- Douglas Pavlicek (Doug Fir) character analysis

- Adam Appich (Maple) character analysis

- Mimas character analysis

- Meaning of the characters’ tree names

- Dr. Patricia Westerford character analysis

- Ray Brinkman and Dorothy Cazaly character analysis

- Theme: legal rights for nature

- Theme: humans are part of nature

- Neelay Mehta character analysis

- Dr. Westerford and “unsuicide”

- Ecofiction in video games

- The role of hope in “The Overstory”

- The significance of multiple characters and why climate action needs everyone

- “The Overstory” ending analysis and our take on “Still”

- Our favorite aspects of “The Overstory”

- Is “The Overstory” literature?

- “The Overstory” paints a realistic picture of activism and its dangers, especially for indigenous people

- Should you read “The Overstory?”

- What you can do to help

- Recommendations

About the creator

Richard Powers is an American novelist from Evanston, Illinois and the author of multiple novels, essays, and short stories. A graduate of the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign for both his bachelor’s and master’s degrees in English, Powers is known for his sprawling novels that often incorporate elements of science fiction and speculative fiction. At the time of writing, The Overstory is his most recent novel, but he is also known for The Echo Maker, which was a finalist for the Pulitzer Prize for Fiction. In 2021, The Hollywood Reporter announced that The Overstory will be adapted for a Netflix series by David Benioff and D.B. Weiss, the creators of Game of Thrones. Richard Powers lives in the foothills of the Great Smoky Mountains.

Official website: http://www.richardpowers.net/

Transcript

Lovis: Well it’s nice to meet you.

Forrest: Yeah. Nice to actually talk to you.

Lovis: Messages back and forth, but face to face. Well, virtual face to face.

Forrest: Yeah. I was about to say, I don’t even…can’t remember the last person I actually talked to face-to-face. It wasn’t just like immediate family, which is weird. It’s yeah. It’s been like almost a year. My wife and I were talking about it last night. We were just like, oh my God. Yeah, it has almost been a year and very, very strange. I don’t know what the timeline was like in the UK or in Scotland, but…

Lovis: Well we went into lockdown kind of mid to late March.

Forrest: Yeah, it was like the same here.

Lovis: So yes, I am Lovis Geier. I run a YouTube channel called Ecofictology where I talk about everything and anything ecofiction, mostly focused on how it can be used as a science communication tool, kind of—a way to access a new audience with some scientific facts for people who don’t really read the academic papers but who are always taken in by a good story. And maybe can ninja some science into there, into ecofiction. So that is kind of, kind of what I focus on with Ecofictology. Today we’re doing something a little bit different. Normally, my book reviews are just me, but today I have a very special guest. This is Forrest Brown. And we’ve connected over the Rewilding our Stories Discord server and realized, you know, there’s really no reason why we shouldn’t do a collaboration video. And we both just finished The Overstory. So we thought this is the perfect opportunity. So welcome, Forrest. Thanks for being here.

Forrest: Hey, Lovis, thank you so much for having me. I’m super excited to be on the show. A little nervous, but excited. Yeah.

Lovis: Yeah, that’s, it’s a shared emotion. We’re good. Yeah. And who better to talk about a story called The Overstory. And it’s all about trees and with someone whose name is Forrest Brown.

Forrest: Oh, my gosh. Somebody—when I was doing an interview recently, after it was over, somebody was like, “I have to ask, is Forrest your real name?” I was like, yes, it is. I didn’t just make it up because it sounds like trees.

Has this info helped you?

Stories for Earth is and always will be a free resource to help people imagine brighter futures through the material we discuss. It’s also created and paid for by one person! Apart from occasional affiliate revenue, donations from people like you is the only way Stories for Earth remains financially feasible.

Lovis: But it’s so fitting, isn’t it?

Forrest: Synchronous? Yeah. Happy coincidence.

Lovis: Yeah. Well, why don’t you do a little introduction to what you do, because you’re also very active in the ecofiction community. Let everyone know what you’re what you’re up to.

Forrest: Yeah. So hello Ecofictologists and also Stories for Earth listeners. My name is Forrest Brown and I make a podcast called Stories for Earth, which is a podcast that’s all about just climate change and pop culture, really just climate change depicted in any kind of work of fiction. And we are medium-agnostic. So I talk about books. I talk about movies like I haven’t done a TV show yet, but I’ll do it one day.

Lovis: You did a music album, didn’t you?

Forrest: Yeah, I just did one. It’s coming out this coming week. It’s on Infest the Rat’s Nest by a band called King Gizzard & The Lizard Wizard, who are like an Australian psychedelic rock band. Yeah, that was like a lot all in one sentence.

Also read: “Infest The Rats’ Nest” by King Gizzard & The Lizard Wizard

Lovis: Did you, did you have to practice how to say that so that you didn’t get tongue tied?

Forrest: Yeah, it’s like one of those say it five times fast kind of band names. But yeah, it was…had to like go slowly whenever I’d say King Gizzard & The Lizard Wizard, but yes.

Lovis: I love it. Definitely going to listen to that episode. Yeah. I’ve been listening to the podcast for a little while and I love it. It’s so good, it’s so good to spread, spread my, my horizons a little bit. Just out of the world of just books. Today we are talking about The Overstory by Richard Powers. And um, I read this. It was a library book, so I don’t have the physical book to hold up to show you.

Forrest: I was going to ask if you had the UK cover version. I wanted to see it.

Lovis: No, no, I don’t. I don’t even know what the, what the cover looks like. I only know the one cover the one that has like the brown and. Yes, that’s one that’s, that’s the cover. Yeah.

Forrest: It’s a cool cover.

Lovis: It is, yes, so this is a really—it’s one of those stories I didn’t want to do a regular book review of this one because it’s so—I just didn’t really know how to put it into such a short discussion episode. It’s just one of those books you have to talk to someone.

Forrest: Yes, I felt the same way. That’s why I hadn’t done an episode on it yet. I finished reading this…when did I finish reading it? It’s been a long time, actually. It was months ago. It was last year. And I took a really long time to read it, which we’ll probably get to you while we’re talking about it.

Lovis: All will be explained.

Forrest: But yeah, like you were saying, it is just a thick book. It’s like, I don’t know, like eight hundred pages or something like that? There’s a lot going on. There’s nine main characters, which is a lot. Yeah. And it covers decades. Has a lot to say. So yeah I’m kind of in the same boat as you, felt like I had to talk it out with somebody else about it.

Lovis: Yeah. We’ll get along fine. We’ll be fine. But that actually brings me to a spoiler warning because normally my book reviews are spoiler free, but because we’re just going to be chatting, we’re not really going to censor ourselves. So there may be spoilers contained in this video. If you don’t want any spoilers and you might want to stop watching now. Just take our recommendation that you should read The Overstory by Richard Powers it’s a great book.

Forrest: And come back in six months when you finish reading it.

Lovis: Yeah, exactly. This is one of those episodes that you can come back to. But from here on out, there might be spoilers, so watch out.

Forrest: And by “might be,” we mean there are going to be spoilers.

Lovis: Yes, there are going to be speaking.

Forrest: Speaking of spoilers, should we spoil some of the book by providing a summary?

Lovis: Let’s. I’ll leave that, I’ll let you take it away if you like.

Forrest: Oh gosh. Yeah. So like we were saying there’s a lot going on in this book. It’s a very long book. It’s a very good book. I really enjoyed it. So yeah, the story, the book really starts by introducing our nine main characters and that’s really like the first, what, first half of the book? It’s a pretty solid chunk of the book is just introducing the characters.

Lovis: That’s what I thought. That’s why it was a little bit, it’s one of those books that, like, you pick up speed as you go through it. And the first half, like one of the big pieces of advice that I would give people reading this book is just stick with it, just don’t give up, because it is kind of you lose the speed a little bit if every chapter you’re switching to new perspective. And like at first, they kind of, you learn so much history about these characters. You’re like, when is something going to happen? It is all necessary and it all is packed full of symbolism and things that just get passed through the generations. So. Just stick with it.

Forrest: Yeah, yeah, and like each introduction of the character is probably like the length of a novella almost it’s pretty long, like we say chapter, but it’s like so-and-so was born in this year and then here’s the 30 years leading up to when this actually matters to the real story of this book. But it all kind of, it’s kind of cool how it all sort of coalesces. And you get to see how the different character timelines eventually, I guess, kind of intersect. And then from there we like see the main story of The Overstory, which begins like after all the characters have finally met or are starting to meet, I guess. And actually some of the characters don’t ever meet. I should say that too.

Lovis: No, they don’t. But they’re like they’re all kind of intertwined, like something happens over here and it affects something that’s happening over here. So eventually it is kind of, you’re moving forward in a, you know, maybe a little wavy, but you’re moving in one direction. Yeah, but for the first half you’re kind of jumping around. But the thing that every…every character storyline, it starts with a tree. And that is something that I thought was really beautiful, that just every, every family was so affected by a certain tree.

Nicholas Hoel (Watchman) character analysis

Forrest: Yeah. And I actually, I was like preparing for this episode this morning, like frantically going back through the book and trying to find which trees were with which people. But yeah. So I guess we could just name the characters and maybe briefly kind of introduce what is going on with them. So I think yeah, I think the first person that we meet is Nicholas Hoell. I don’t know how to pronounce his name. He lives in Iowa and the book just kind of details a very long history of, you know, like I think how his grandfather emigrated from Sweden or a Scandinavian country. Yeah. Immigrated to the United States. They have like this homestead in rural Iowa. And throughout Nick’s family history, they’ve been, there’s been kind of this like folk art project sort of where they’ve been taking a picture of this one tree for generations. And you can kind of see like do like a time lapse, I guess, of how the tree has grown over the generations. And this was an American chestnut tree, which all the reviews and the summaries I was reading kept saying it was a chestnut tree, which it has chestnut in the name, but it is specifically an American chestnut tree, which is significant because those are basically extinct now. And if you say like a redwood tree, everybody will probably know what you’re talking about. These big, huge behemoth trees grow on the west coast of the United States and up to Canada as well. But the American chestnut was kind of like the East Coast version of a redwood, and we’ve basically lost all of them now, which is just horrible. There are some efforts by some universities in the United States and in Canada to sort of like revitalize the species and restore it. And they’re starting to actually make progress on that, which is pretty cool. It’s pretty amazing that they’ve been able to do that. But basically there was like a blight and it wiped out like. All of the trees from Canada all the way through, like the American Midwest, which is just an enormous swath of land, just like tons and tons and tons of trees were lost. So, yeah, this American chestnut tree that Nick Hoell has is kind of like one of the last of its kind. And it’s really special that they’ve been able to take pictures of it for so long. But yeah, Nick is an artist and he’s kind of like. Fallen on hard times and ended up back on the family farm in Iowa after—I think he was in Chicago doing his art thing and then, yeah, kind of wound up back there. So when we meet him, when the story actually starts, he’s kind of just like waiting on the insurance money from his family to run out. He’s the last person left, essentially, like all of his family and friends are gone. And he’s just kind of living the sad little life on the farm, painting pictures.

Also read: “Parable of the Sower” by Octavia E. Butler

Lovis: And he just has these memories, this flipbook of memories. And he just he just feels kind of the weight of past generations. And he paints all these trees and he does all this art that reflects his kind of fascination with nature, because he also he, he was the one that did the little. Oh, no, that was a different, you know, the little ant things…

Forrest: It’s so easy to get them mixed up. I’m probably going to the mixed up at some point.

Lovis: So when we meet him he’s kind of a down in the dumps. Waiting for his life to really start. Yeah.

Olivia Vandergriff (Maidenhair) character analysis

Forrest: Yeah so the next character is Olivia and she—Olivia Vandergriff. Excuse me. She’s a college student. I don’t remember where she is living when the story starts, but yeah, she—

Lovis: There’s so many details to retain in this book. That was not one of the ones I chose to retain.

Forrest: Olivia is a college student and she’s kind of painted as like this typical, like kind of cynical artsy college student. And one night she, I guess, is back in her house that she rents with some other students and she’s getting out of the shower, I think. And as she’s like getting out of the shower, she turns on the lights and it’s like an old house, so like the wiring. The electricity is kind of like, ehh, it’s a little iffy. And yeah, she like, basically electrocutes herself and nearly dies. So as she’s kind of like in this in-between state, like between life and death, she has sort of like an epiphany, I guess you might say. And these like beings of light kind of come to her and are telling her she needs to go somewhere. And I—we never really find out what they are. I don’t know if it’s just like a hallucination, like if she’s kind of fried her brain in some way.

Lovis: I don’t know but the voices just stay with her throughout the entire story and they tell her like, yes, you’re going in the right way. Or you should, you should stop along the side of this road and follow the sign for the art gallery down there.

Forrest: Yeah. And that leads her to Nicholas. Yeah. On his farm in Iowa. So. Yeah. They…I don’t know how they wind up…I can’t remember now how they wind up deciding that they should go on this trip together. But I think for Nick it’s probably just like “Yeah sure, got nothing else to lose.”

Lovis: So I guess first she has to convince him that she’s hearing these voices and that she’s not just. Off on a wild goose chase, but she has a goal and a motivation. And so they’re headed west to join with some protests that are protesting the clearing of old growth forests for the lumber industry.

Forrest: Yeah, and I was trying to go back and find I don’t think that Olivia actually had a like a special relationship with a certain kind of tree. I think for her it was maybe another tree, which we’ll probably talk about in just a minute. But other than that, it was like the voices, which I guess are kind of like, like spirits of the trees, almost is kind of how I interpreted that.

Lovis: Yeah. Some kind of natural beings. Nature’s voices kind of speaking to her, telling her where she needs to be in order to set some kind of domino effect in motion.

Mimi Ma (Mulberry) character analysis

Forrest: So they go off and they head to I guess like Oregon, California. And then we’re introduced to another character, Mimi Ma who is, she’s the son of a Chinese immigrant or Chinese immigrants.

Lovis: She’s the daughter of Chinese immigrants.

Forrest: I’m sorry, I said son. She’s the daughter of Chinese immigrants. And her father, he was really big on taking them to go see the national parks. And he had this mulberry tree that was in their backyard. When they were growing up, she and her sister, growing up, and that was always like a really big thing in her life, was that mulberry tree and she kind of like associated it with her father. Because he just kind of doted on it all the time and it was kind of like a prized possession, I guess. So she’s an engineer and I think she’s living in Portland, Oregon, when we meet her. And yeah, there is like a tree outside her window that she’s sort of attached to.

Lovis: Well, there’s like this this grove of pine trees, and that’s where she goes and has her lunch and kind of. In the rest of this kind of developed business park, it’s like the one little patch of green. And her father had this ancient scroll that he brought from China that had like paintings of…and I forget the words now. But paintings of these old wisemen and trees and and kind of words of wisdom and things that she’s locked away, but is still kind of in the back of her mind.

Douglas Pavlicek (Doug Fir) character analysis

Forrest: Yeah, it’s like one of the only things she has left from her father. So it’s really important to her. Yeah, that’s kind of around the time when she meets another character named Douglas Pavlicek. And Doug is a Vietnam veteran, Vietnam War veteran. And after—also one really important detail about Douglas that I feel like a lot of, like if you go online and you read like a summary of this book or if you read a review of this book, a lot of people for some reason leave out the fact that Douglas was a participant in the Stanford Prison Experiment, which is kind of a huge detail to leave out.

So, like, if you’re not familiar with the Stanford Prison Experiment, it was this, I guess, kind of like a psychological experiment that was done in the I believe it was the 60s, early 60s. Don’t know the dates, but, yeah, there’s there’s a good movie about it that I think you can watch on Netflix or Hulu. But yeah, basically they, these group of researchers at Stanford University in California, they got a group of volunteers who were mostly like young, young men, and they created like a prison scenario where some of the people were assigned to be prisoners and some of them were assigned to be prison wardens. And it was kind of just like a study of how humans behave in situations like that, where there’s a power dynamic. And yeah, long story short, like the wardens became horrible and they were like abusing the prisoners and it got really, really out of control and they had to shut down the experiment. So, yeah, Douglas was part of that! And as you might imagine, that had a pretty profound effect on him. And like the way that he…like his world view and the way that he views other people, the way that he views humanity. So, yeah, that’s kind of like in the background as we’re going through his story. But he ends up going to Vietnam. There was actually a tree in Vietnam that was kind of his introduction to trees, I guess, which was like the banyan tree, I think.

Lovis: Yeah. Because he fell—he…his plane or helicopter. I can’t remember…some kind of flying craft was attacked and blown out of the sky basically. And he he fell and was caught by this banyan tree. So he was basically saved by this banyan tree thing, I think his parachute got caught in it.

Forrest: After the war, he obviously comes back home and he realizes that deforestation is a really big problem in the United States at that time, still is. So he kind of devotes himself to trying to reforest different parts of the country. Yeah. And then he has a really kind of sad realization.

Lovis: It is really sad. It’s really sad. He spends I think it’s decades that he spends just walking along and planting a tree and he gets paid like a penny, a seed or something miniscule. And and he reaches the point where he plants, was it fifty thousand trees? It’s a lot of trees. And he goes to, to celebrate in a pub and somebody is like well. You know, who’s paying you to pay to plant those trees are the people who are going to chop them down and when they’re big enough to turn them into lumber. You’re just feeding the machine. And this, of course, breaks Douglass’s kind of sanity and his idea that he’s doing something good and then he realizes that actually. It’s not making any difference to like replacing what’s been lost.

Forrest: Yeah. He’s just working for the logging companies who are, this is like part of forestry, which is a very deceiving field title because it sounds like something it’s like yeah, it’s basically just like studying how you can make money off of trees. But yeah, he’s just like planting trees so that they can eventually be cut back down for lumber, you know, in so many years. But yeah, this is kind of when like after he has this realization that’s I guess kind of when his story and Mimi Ma’s intersect and he’s in Portland because they’re starting to cut down the trees in the clearing that Mimi takes her lunch in. And I think he actually gets hit by a cop or somebody when he’s like trying to protest.

Lovis: Yeah, he tries to intervene because they posted something that says they’re going to they’re going to cut down these trees. You should go to the meeting in a couple of days time if you have a problem with that. And so, Mimi’s like, well, I’m going to go to the meeting. I’m going to protect my trees. And then they actually cut down the trees, like in the night before the meeting. So they haven’t actually given anybody a chance to say that they have a problem with that. And Douglas just happens to be there, I think, and intervenes. But of course. You wonder where his problem with authority comes from. But so and of course, he’s not supposed to do that, so he gets sent to jail, I think for a couple of days, and then when he gets out, obviously the trees are cut and Mimi is there and is heartbroken because they’ve cut down these trees that reminded her of her father and the places that they used to go when she was a child.

Forrest: Mm hmm. So this is kind of like the I guess, like the catalyst for when Mimi sort of starts to become radicalized, I guess you could say, and like Douglas was involved with these protests. So they kind of become pals and protest buddies and they start going to like these protests to object to the logging companies coming in and cutting down all the old growth like redwood forests in the Pacific Northwest. And, yeah, that’s…this is kind of around the time when all the characters or at least the characters that do meet end up meeting each other. There’s a couple more that we should talk about.

Adam Appich (Maple) character analysis

Lovis: Yeah, definitely. I think the last one that actually joins those, that group is Adam.

Forrest: Yeah, Adam Appich. Yeah. And he’s a psychologist.

Lovis: Yeah. Yeah, he’s a student. He’s studying psychology and he chooses…for his, it’s a masters, I think, for his thesis topic he chooses to study the protesters. And it’s a question of. Well, I don’t even know how to phrase his question, but the question of like, why are people standing up for trees? What is it about trees that people feel pushed to—sometimes violence—to protect them? Yeah, and also the other side, everybody cutting down the trees. How do they not…you know, what are they not seeing about the trees that make them cut them down? I think is kind of what he was doing. So he was going around interviewing a lot of the a lot of the protesters.

Forrest: Right. He was kind of interested in the psychology behind it. But, yeah, he kind of ends up getting caught up in all of it and he kind of falls prey to the very psychological phenomenon he’s studying. And he ends up actually becoming a protester, too.

Mimas character analysis

Lovis: When he meets Olivia and Nick up in the tree platform on one of the oldest trees on the West Coast, a tree called Mimas. This storyline…

Forrest: A moment of silence for Mimas.

Lovis: A moment of silence for Mimas.

Forrest: Pour one out for Mimas.

Lovis: This is one of the most heartbreaking parts of this book.

Forrest: I know it was like soul crushing.

Lovis: I think when this happened, I nearly I was like, I don’t want to finish this book! You built me up to these heights of hope and then…ugh.

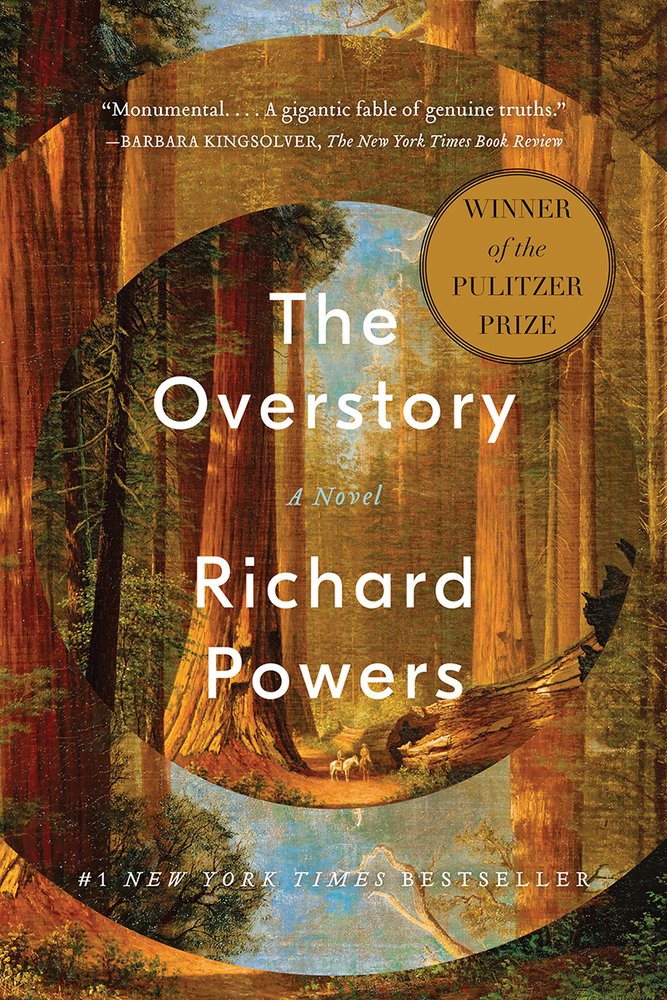

Forrest: Yeah, so Mimas is like this, I think it might actually be based off of a real tree, although in real life we actually don’t know where this tree is.

Lovis: Probably better that way.

Forrest: Yeah, I think that’s why we don’t know it is so that they can protect it. There is like this really, really, really big old redwood tree somewhere on the US West Coast. Like I said, nobody knows where, but it’s like massive. And these trees are really, really, really big like you can. There are places like in Redwood National Park where unfortunately some genius was like, oh, I should cut a tunnel through this. You can drive your car through it one day and you can do that. But surprisingly, the trees survive. They’re actually pretty resilient, but still not good. But yeah, Mimas is like this tree, kind of like that. It’s this big, huge, like behemoth of a tree. I kind of saw a lot of parallels between it and like the Tree of Life in the Genesis story in the Bible. I kept thinking about that. I don’t know if that was the intention or…I guess like a more…how do I put this? Maybe a different way of thinking about mimesis, like Big Tree of Life at the Animal Kingdom at Disney World, which is a very American capitalist way to think about it. But yeah, I kept thinking of that. That tree is like plastic. It’s so sad, but yeah. So Mimas is like this giant tree and Nick and Olivia and then eventually Adam are trying to protect it from the logging companies who want to come in and chop it down for lumber.

Lovis: Yeah. Because they’re cutting just, they’re just clearing swathes of land around Mimas, which is all old growth. And so they’re doing a tree sit protest. So they don’t come down off the tree in the hopes that the logging companies then can’t cut down the tree because then they would be responsible for three deaths. But of course, I mean, well, they actually stay up there for, like a year or something? They stay up there a long, long time

Forrest: Like kind of an unbelievably long time.

Lovis: So they just become these, like, tree creatures.

Forrest: Yeah, they kind of do. I don’t really understand the physiology or how realistic this would be, but I’m sure like impossible. But yeah, they were like living on this sort of raised platform, almost like a tree house, I guess, up in Mimas. And there were like huckleberries, I think? This tree was like so big that basically it had its own ecosystem, like at the top of it.

Also read: “Ishmael” by Daniel Quinn, Climate Change, and Moving Beyond a Vision of Doom

Lovis: Yeah, in like little crevices, water would collect and there were like fish up there there or something. And they had berry bushes growing and everything. So this tree is gigantic and it’s like what did they say? Like two hundred meters tall or something.

Forrest: Very, very tall. Yeah. It was like you could see the clouds when you’re up in the top of—like you were looking down on the clouds almost.

Lovis: Yeah. So they were up there and they were just watching the land around them get cleared by these like bulldozers and loggers and, and the, the men, the loggers at the base of the tree were always shouting up to them, trying to convince them to come down. And Nick was drawing the whole time and he was creating art and he was sending the pictures down there to show them what they were threatening and what they were going to lose if they cut down this tree and then Adam comes up to interview them. And of course, that is when he gets swept up in the whole movement and he sees kind of the intrinsic value of nature, I suppose, and he sees the destruction and desolation left behind him when companies get hold of old growth forests. And eventually they cut down Mimas. This was the thing! This is the thing that just, it just destroyed me, just this whole epic battle and then they lose! And the heroes aren’t supposed to lose. But it was like, you lied to me when you made me read this book and the heroes are supposed to win, and then they lost. I couldn’t believe it.

Forrest: Yeah. I felt very betrayed as a reader at this point in the story.

Lovis: How dare you? How dare you kill Mimas!

Forrest: Yeah, because he spends so much time talking about Mimas and really, you know…

Lovis: Creating this character! He killed a main character!

Forrest: Yeah Mimas was a character. So yeah we said there are nine main characters. I guess there’s really like 10 if you include Mimas. He spent so much time talking about how special Mimas like how beautiful it is, how it’s just kind of life-sustaining being and then, yeah, the logger win, and basically the protesters were doing all of that for nothing. So yeah that was a pretty crushing moment of the story, and I will not lie to you. It doesn’t really get a whole lot better from there. This book is. Yeah, it’s…this is this is why it took me so long to read it! But yeah. So they cut the tree down and then after this I think this is about the time when they meet the last two protesters, Mimi Ma and Douglas, or maybe they met a little bit before this?

Lovis: This has really lit a fire under them now. And so they head north because now they have…I think yeah. This was in California, I think. And then they head to Oregon. And they meet up with Mimi Ma and Douglas for further protests.

Meaning of the characters’ tree names

Forrest: Yeah. So somewhere around this time after the, after all of the protesters finally meet, they, I guess it’s to protect themselves because it is pretty dangerous to be an environmental protester, especially probably in the 90s when the collective consciousness around like what we’re doing to the environment had not really clicked for a lot of people yet. But yeah, so they kind of take on these aliases, which are tree names. So it’s a little bit like a full circle moment in some ways. They go from admiring these trees like earlier in their lives to then like taking on their names. So in some ways they kind of like embody the trees in that respect. But yeah, Nick becomes well, his name is Watchman. He doesn’t actually take a tree name, but again, like he had the American chestnut and then Mimas and then Olivia becomes Maidenhair.

Lovis: Yeah, this was, this was the way that the protesters referred to each other because they preferred not to use real names. They decided to take on some kind of natural name. And Watchman, I think he he took inspiration from—or Olivia because she named him—and took inspiration from the way the trees just watch. So he was kind of the Watchman. He just represented all the trees.

Forrest: So modest. And then Mimi was Mulberry, which is kind of a no-brainer because of the tree that her dad used to have in their backyard. And then Douglas probably picked the worst alias out of all of them.

Lovis: Because he became Douglas fir?

Forrest: Yeah, he had—his name was in the name of the tree species.

Lovis: He couldn’t be Banyan? Come on!

Forrest: Yeah. Banyan would have been a cool one, but yeah, he was Doug Fir instead, which maybe did him some disservice later in his life but. Yeah so, and then Adam, I can’t, I was trying to remember if Adam, I was trying to find it in the book, if Adam took an alias. I thought that it was Maple because.

Lovis: Yeah I think so. I think he was Maple.

Forrest: I didn’t mention this back when we were introducing Adam, but I guess his kind of connection with trees earlier in life was…this was kind of cool. He he had a bunch of siblings and when he was young, his dad basically was just like, I’m going to plant a tree for each one of my kids. And then I think Adam was the one who got to pick who was which tree, basically. And then he was Maple. So that’s kind of where that name comes from. Those are all the characters that—there are some that meet like very briefly later on. But those are kind of like the main group of characters that are together, I guess. And then there are some other ones as well.

Lovis: Yeah. So, whoo.

Forrest: I know, that feels like an entire book right there.

Lovis: I know, that’s only half the flippin characters.

Forrest: I know. So maybe we can go through these a little bit quicker because I feel like they don’t get as much screen time, if you will, as the other characters do.

Dr. Patricia Westerford character analysis

Lovis: Yeah, I guess so. But I guess the the logical next step would be Dr. Westerford, because she’s involved with the court case against these protesters, so she gets called into as a witness, an expert witness, because she is a botanist and she’s a plant biologist and has studied plants, her whole academic career. Her major discovery was that plants communicate and that they, they have their own language, that they’re not these inanimate objects that we think they are. And so she discovered that they send, they send cues to each other so they can communicate when they’re being attacked so that other plants and trees and everything can deploy their defense mechanisms. And yeah, so basically, she was trying to give them a little bit more identity, I suppose, and saying that they communicate and the scientific community just dumped on her. They just said that she was crazy and that her findings were completely unfounded and couldn’t be backed up and that they were ridiculous. And so her name was pretty much slandered. And and she she kind of pulled away. She pulled away from the scientific community completely and vanished into the forest for a while to hide.

Forrest: Yeah, she was, like, super depressed.

Lovis: Yeah, because she couldn’t get a job anywhere, nobody wanted to hire her.

Forrest: Yeah, she was kind of a laughing stock.

Lovis: Yeah. Which was so sad. I mean, you kind of hope that the push towards something, towards seeing nature as something other than like can’t feel any pain or can be used by humans would come from the scientific community and then it’s the scientific community that just destroys it, which is so sad for me.

Also read: “Weather” by Jenny Offill

Forrest: Yeah, I know. Yeah. Because you’re a scientist.

Lovis: I am a scientist. And I was like, no. Because obviously, she ends up being right. That is exactly what happened. It’s been proven multiple, multiple times. They can see, they can hear, they can feel. They have all kinds of cool adaptations to take in their environment and communicate to each other so that if.

Forrest: Yeah. And cooperate too.

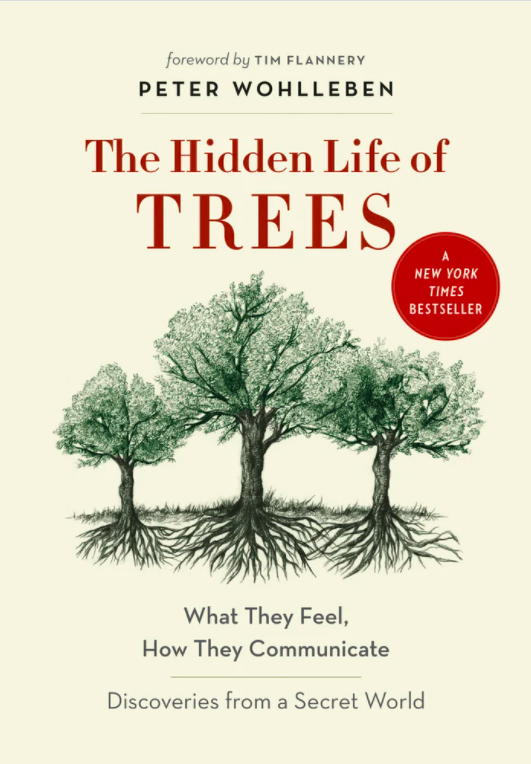

Lovis: Yeah. So that they can cooperate and they, they act as a community and it’s, and it’s all true. So she was vindicated in the end. But still, she had to go through most of her academic career being this laughing stock. But I guess. Silver linings, it did, it did drive her to meet the people who are working in the forest and kind of solve things more her way. And and she started writing books. Which made her a very sympathetic character to me. She wrote books and tried to teach nonscientists everything she knew about trees.

Forrest: Yeah. And she eventually I think that, just like a side note, I believe that Richard Powers, the author, actually based this character off of two real life scientists. So one of them, I’m like so irritated with myself because the name is escaping me. But she is a Canadian scientist who has kind of done similar research in real life. And then the other one that I’m thinking of is a…I think he’s a…I’m trying to remember his exact title. Basically, he works in like managing forests in Germany. And his name is Peter Wohlleben. But he wrote a book called I think it’s The Hidden Life of Trees that was published a few years ago. And like here in the US, it was like all on like NPR’s best books of the year lists and stuff like that. I don’t know why, but yeah, it was kind of like a surprising bestseller, which also happens to Patricia Westerford. And all these people are like, wow, that’s amazing. Like I had no idea trees could talk to each other and yeah, she’s yeah. That’s kind of how she’s vindicated later in life and basically gets a lot of speaking gigs and stuff like that going around the world talking about this.

Lovis: Yep, and eventually that’s why she gets pulled into the court case against the protesters because she’s. She knows so much about trees and she is brought in to kind of testify to the value, the natural intrinsic value of leaving trees where they are and not cutting them down. So basically, trying to defend the, the protesters stance in an economic, financial way, because sadly, that is the kind of language that speaks to people who make this decision. And that is the language that they speak, so that is the language that we also have to speak. So she was making the case that you should just leave forests alone because of all these things that they do. They give you medicines and they produce air and they clean your water and they do all of these wonderful things that you don’t even realize until you’ve cut them down and then they stop doing it. And then you have to figure out a way to do it yourself.

Ray Brinkman and Dorothy Cazaly character analysis

Forrest: Yeah, yeah. I guess that might be a good segue to talk about two other characters who appear in the book, which would be Ray Brinkman and Dorothy Cazaly, I think is how you say your last name, but they’re a husband and wife pair and Ray is a—I think he was an intellectual property lawyer. And then Dorothy was a stenographer, which is kind of an interesting career. But, yeah, basically they, they never have kids. And I think Dorothy is kind of upset about that, that they never have children, whereas I feel like Ray was more of the one who was like, it’s okay. Like you don’t have to have children to have a meaningful life. Like we can fill our lives with art and like knowledge and, you know, sort of that kind of more like a humanistic, I guess, approach. So, yeah, later in life, Dorothy is like having an affair with Ray and with somebody else, like a colleague or something. I forget his name, but. Yeah, and then right after she tells Ray that she’s like going to leave him, he conveniently has a seizure and is basically bedridden for the rest of his life.

Lovis: So, yeah, he’s almost quadriplegic, isn’t he? He can like move one hand but he can’t really move his face and he can’t really speak, he can make some sounds and eventually she starts understanding the sounds. But yeah, she, he’s completely dependent upon her which, and obviously at that point she doesn’t feel that she can leave him because he needs her. So she’s she feels kind of stuck and so they’re looking for ways to, to get through the days. And she’s reading to him because they always both had a fascination with books. And they read to each other and eventually they pick up this book this Everything about Trees book that Dr. Westerford has written. And, and just opens a whole new world for them. And they look out their window and they try and identify all the trees that they have in their garden and in their neighborhood. And they realize, wow, our garden is not as natural and wild as it could be. And so they go on this rewilding project, which I love.

Forrest: Yeah, that was a cool story line.

Lovis: It took a while to get there! I was like, where are we going?

Forrest: I know. I was like, what’s the point. Yeah. But yeah, this was an interesting thing that got brought up because like, like I said, Ray’s background was in law. So they kind of get into this legal battle with the city, I think. And because they’re just like, screw it. Like we’re letting our yard go natural, like we’re going to let whatever wants to grow in the backyard grow or even the front yard, too, I think. So, like you said, they were like rewilding their property.

Lovis: I think I have, I think I took a screenshot of that page. Of course, now I have to find it. Right.

“If you could save yourself, your wife, your child, or even a stranger by burning something down, the law allows you. If someone breaks into your home and starts destroying it, you may stop them however you need to…He can find no way to say what so badly needs saying. Our home has been broken into. Our lives are being endangered. The law allows for all necessary force against unlawful and imminent harm…The planet’s lungs will be ripped out. And the law will let this happen, because harm was never imminent enough. Imminent, at the speed of people, is too late. The law must judge imminent at the speed of trees.” -Ray Brinkman in The Overstory, pp. 497-498

Forrest: That was such a great quote, there are so many good quotes from this book.

Theme: legal rights for nature

Lovis: Yeah, so many good quotes. “The law must judge imminent at the speed of trees.”

Forrest: Yeah. Which is another really big theme in the book, too, that we’ll probably touch on in a little bit. So, yeah, they, they get involved in this legal battle with the city. And just like the quote that Lovis just read, basically Ray starts to kind of make a legal case for rights for nature. And that’s like a whole thing that the book goes into, which is pretty interesting and has a lot of parallels to real life, too. So I know there was some—I was looking for like examples of this in real life. And there are, I think the article that I found was in Yale Environment 360, which is put out by the Yale University School of the Environment. But it was an article about just like how a lot of indigenous peoples around the world are basically kind of petitioning their governments for rights for nature because those are such, it is such an integral part of their culture and their livelihood in a lot of examples. The particular one that I was looking at, I think was in Chile, and it was this huge river in Chile, which the author of the article compared to, I guess, the equivalent of kind of like the Rio Grand in the Grand Canyon in the United States. But in Chile, there are a lot of rivers. So to the government, that’s a good source or like a good opportunity to build hydroelectric dams for energy. So, yeah, the, the Chilean government had built a hydroelectric dam and basically it permanently changed this river. So it’s been turned into like parts where there are huge reservoirs now, which has like led to things like landslides happening. Yeah. And it’s really affected the environment in a pretty negative way, which is so deceiving because hydroelectric dams are like a source of renewable energy. So you’d think it’s a good thing, but it’s kind of complicated. So, yeah, that’s, that’s kind of been a big movement among indigenous peoples around the world. I think it actually may have started with the Maori people in New Zealand.

Also read: Joy Harjo: “Crazy Brave,” “An American Sunset,” And The Land

Lovis: Yeah, yeah. They sought legal rights for a river as well that passed through kind of sacred land. And the government was trying to was trying to develop something around it. And and they, they won I think.

Forrest: Yeah. So that’s a pretty good example, I think, of where. I mean, I don’t know a ton of details about that situation, I’m sure it’s still very imperfect, but it seems to be like the start of a good sort of—I hate to use the word compromise, but sort of like a compromise between like traditional ways of living, like indigenous ways of living, and then like just sort of like Western colonial sort of ways of living where these two have kind of merged now and clashed a lot of times—or most of the time, I should say. But it feels like a good start to maybe sort of. Making up for some of that or reconciling a little bit of it?

Theme: humans are part of nature

Lovis: I mean, a lot of the discussions about, oh, well, how do we get back to nature? There’s a, there’s some talk about going backwards and some talk about developing and going forwards with new methods. And I think it has to be a combination of both. We do have to use new methods because it’s just not going to happen that people are going to give up this convenient lifestyle that we have. But in other things, I think we do need to go backwards. I think especially in this idea of how, how important nature is to us culturally and how much value we lay on it. I think we do have to go backwards to a time when nature was much more culturally important

Forrest: And wasn’t just seen as a commodity or a “natural resource.”

Lovis: Yeah, exactly it’s not beneath us, it’s around us. And we’re part of this system rather than just the system is there for us to use. And and so I think this is a really good, a really good start. And you sent me a really interesting quote by the author for the kind of the motivation behind behind writing the book. And that is kind of linked to this.

We’re part of nature, not apart from nature.

Forrest: Yeah. It kind of comes in here as well. I just had it up. Or do you have it up?

Lovis: Yeah, I have it. Richard Powers said [in an interview with SIERRA Magazine], “The real question for humanity now is whether we can find stories that confront what it will take for us to live among non-humans in a permanent way. Writers need to turn their eyes outward and start asking what kinds of values we would need to develop, what myths we need to tell ourselves, and what perceptions we need to cultivate to truly live here and not in an imaginary, self-exempting place that externalizes all costs and acknowledges only private and individual meaning.”

Forrest: Yeah, retweet Richard Powers!

Lovis: Which is a much more beautiful powerful way of saying, we really need to stop being so egotistical and realize that we’re part of a bigger system and appreciate the bigger system.

Forrest: Right. We’re part of nature, not apart from nature I guess.

Lovis: Yeah, exactly. Yeah.

Forrest: So, I think that that might be a good place to, I guess, put a pin with Ray and Dorothy and kind of come back to them a little bit later. But just to finally finish talking about all of our characters.

Lovis: An hour later we’re finishing the last storyline!

Forrest: That’s the episode! Hope everybody had fun.

Lovis: You don’t need to read this book now, you’ve heard it.

Neelay Mehta character analysis

Forrest: We just told you the whole book. Good thing we put a spoiler warning at the beginning. But yeah, the last the last character is Neelay Mehta, who is a video game developer, which I thought was a pretty cool narrative. But he, like all the other characters, he also has a relationship with trees, except his is kind of a bad one at first. He basically…I forget what he was doing…he was kind of like doing something mischievous, I think, and he was trying to hide. So he climbed up into a tree and then he fell out of the tree and broke his back and became wheelchair-bound. And he was like paralyzed from the waist down for the rest of his life. So, yeah, he ended up becoming a very successful video game developer. He kind of becomes like a sort of like Silicon Valley magnate, I guess, or like a billionaire and makes this really successful video game franchise called Mastery, which I guess I don’t know what the modern equivalent would be, would kind of like Minecraft, I guess, something like that, or like The Sims?

Lovis: I guess so. It’s basically a world that you as the player influence what it looks like and how it develops and how it builds. So you have power as a player to use up resources and, and things like that. And he took inspiration from trees. He wanted to he wanted to replicate kind of the intricacy and the complexity of the perfection of what they are and what they create and the balance that they have. And a myriad of different things and processes happening at the same time. And so he yeah, he created this world that people could escape to. That was hugely complicated and made it, just became a new addiction for people to disappear into this world rather than reality, which is what he did too because he didn’t like his reality so much.

Forrest: Yeah, that’s a good point.

Lovis: And so he he kind of became who he really wanted to be in this world, but eventually kind of realized that. What people were asking for and thinking, “Oh, what will make us more money, and how will we keep people addicted to this game?” What it created was just a replica of our world now where people are using up resources and…

Forrest: All the worst parts of our world.

Lovis: Yeah, we just we just took the worst parts of our world because that is all we understand. That’s how we know how to comprehend a world, I suppose, in a capitalist kind of way. And he was like, no, this is wrong. But he only realized it after he had millions of people kind of addicted to this game. And so he had to.…

Forrest: And a board of directors who was very not on board with his new idea.

Lovis: No, because the new idea would lose them money! Heaven forbid!

Forrest: Yeah cause they already have like billions of dollars.

Lovis: There’s like these 30 year old billionaires sitting around a table and he’s like, well, I think we should do something that doesn’t, you know, pollute people’s minds. And they’re like, nah, I’d rather continue raking in my money.

Forrest: Yeah, of course. So I forget, was this, um. So yeah, the game was Mastery and like you’re saying, like it got to a point where basically he was just like, oh, I don’t know how to make this any different. Like we kind of have run out of tricks. So then I think it, was it after he saw Patricia Westerford speak that he had this kind of change of heart and wanted to change the video game design? Or was it around the same time? I can’t remember now.

Lovis: Well, he met someone in-game that that was like, “Oh, I thought this was going to be something great, but actually, it’s just turned into another money machine.” And Neelay was like, “What are you talking about? My game is great!” Yeah. But he was like, the game doesn’t show us anything better. And Neelay realizes, yeah he’s right. And then yeah I think at some point he sees a speech given by Dr. Westerford, and we also hear about this during her storyline. She, after the court case was dismissed because, of course, it was dismissed, she went around the world collecting seeds from all the tree species that she thought were going to go extinct in the next century or something and created a seed bank in Colorado. And she just traveled the world collecting these trees and she would see the most magnificent trees and ones that were threatened by landscape development or temperature change or just anything human made. And and so she had the seed bank and and she wrote another book and she was invited to this talk, and she basically…the talk was about home redevelopment or something. That was what it was. And it was supposed to be about ideas of how we could rebuild, how we could renovate our world to make it, to make us do better. Her answer was kind of like. “Get rid of humans!”

Dr. Westerford and “unsuicide”

Forrest: Yeah, basically, and this was like one of the big…I don’t want to say climax, but this is like a really big moment in the book. So yeah, Neelay is at this event, which is not very clear from the beginning of the scene, but. Yeah. And it’s kind of told from two different perspectives. So it’s told first from Patricia Westerford’s, Dr. Patricia Westerford’s and then from Neelays.

Lovis: And also from Mimi’s, she was there too.

Forrest: She’s. Yes. Yes. She was there too. That’s right. So yeah, she was, Dr. Westerford was giving this talk, and yeah. Like you were saying at the at the end, basically concludes that like, sort of the best thing that you can do for the environment is not exist as like a 21st-century human living in, you know, like a developed Western country. So she says, I think her last words are here’s to un-suicide. And then she actually takes poison from a tree that she found in the Amazon, I think, and just kills herself in front of everybody. And obviously Neelay was like, “No, don’t do it!” And it was too late. But yeah. So like after that, that obviously probably had a pretty profound and traumatic impact on Neelay, I would imagine, and everybody else who was in the audience. But I think that’s when he like—unless I’m getting my timelines mixed up—that’s like when he really started to push for making this update to his video game to make it more like, oh, you have these constraints now. You can’t just do exponential growth, like now you’re in a closed system. You will run out of resources eventually. That will have consequences. So he was, I guess, kind of realizing that his video game wasn’t as true to reality as he maybe thought it was before, and trying to get people, I guess, to think a little bit more about sustainability.

Ecofiction in video games

Lovis: Yeah, exactly, and gamification is a huge thing, and people are using it now to try and get this message across as well. I did an episode on ecofiction in video games, and there were a few, a few examples of video games that were trying to just send environmental messages, ecological messages. And one of them is called Eco, where it is pretty much exactly like this. There’s a world and you have to save it and you have to develop it. But you have finite resources and it has to be a collaborative effort. You don’t really do things by yourself because you won’t get very far. So you have to collaborate and you have finite resources. And your goal is to not kill everything.

Forrest: Yeah, basically to build a sustainable society.

Lovis: Which sounds so hard. And there was a big discussion about it, whether it was useful because people—because it’s hard, people will stop playing it.

Forrest: Oh okay, interesting.

Lovis: The discussion, I guess, is whether they toe the line enough to make it hard so that it’s a challenge so that people want to beat it, but not so hard that people are like, oh this is not fun.

Forrest: There was another video game that this reminded me of too, which, probably nobody will know what I’m talking about. Like maybe? But when I was a kid, there was this computer game, back when games actually came on, CDs or discs. And it was a Star Wars video game called the Gungan Frontier, which was, of course, made after the most beloved character in the entire Star Wars franchise, Jar Jar Binks. But basically you had to…you kind of got this like virgin world, this planet that was like, had all the conditions for life, but there was no life on it yet. It was kind of like, I guess the…I don’t remember what they call it, but back when Earth was still without life and it was basically just like ocean and like chemicals and stuff in the water.

Lovis: Primordial?

Forrest: Yes, that’s it. That’s what I’m thinking of, the primordial soup? I don’t know. I’m not a scientist. So it’s kind of like that. But you have to basically, like…

Lovis: Go through evolution? Oh my goodness.

Forrest: No, not exactly. But basically, you are like the planter of the seeds of life, I guess. So you are like, you have to build an ecosystem, basically. But it’s very fragile. It was such a hard game. It was kind of like you were saying with Eco. It was so frustrating at times, but it was also super addictive, so I would play it a lot. But yeah, you had to be like, oh, you put too many predators in the environment, now they’re eating all of the herbivores. And oh, you put too many herbivores in the environment, now all the grass is gone and now they’re dying and now the predators have no food source. So it was kind of like that, I guess.

Lovis: That sounds ike a great game that a scientist would love!

Forrest: It was a lot of fun! It was actually before—because I think we had kind of talked a little bit on the Discord about Eco, that video game. And I was trying to see if there was a way that people could still play that game that I was thinking of today. But I don’t really think you can, which is sad. Maybe, maybe it’s like on Steam or something? I don’t know.

Lovis: We can have a little search.

Forrest: Yeah. Anyway, that just made me think of that, it kind of like brought me back to a childhood memory.

The role of hope in “The Overstory”

Lovis: So I think we’ve covered all the storylines now all finally, finally. And so now I guess I guess we can, we can just talk about how how we found it. I mean.

Forrest: Yeah.

Lovis: There’s so many—there’s so much to talk about, there’s so many storylines and so many massive messages that he, that he has, and I guess one of the, one of my big things was that I just felt no hope while I was reading this book. On my channel, I talk a lot about the need for hope in our fiction because the lack of hope is so demotivating. And people say, oh, well, if it’s that bad, then if there’s no hope, then why should I try?

Forrest: It’s just like a video game, it’s too hard.

Lovis: Yeah, exactly! It’s just, I’ll just stop. And actually when I was first. Looking up ecofiction and discovering the genre, a lot of people sent me to The Overstory to search for, because it was a title that they said had a lot of hope.

Forrest: Oh?

Lovis: I do not, and they swindled me!

Forrest: Yeah, you’ve been bamboozled.

Lovis: I’ve been bamboozled! This story is full of scientists and activists and protesters, and—

Forrest: And they all get crushed!

Lovis: And they did. Oh, my goodness! They all lose!

Forrest: Yeah. We didn’t even get to the like the worst parts for the characters, which I don’t think we need to go into.

Lovis: But no, I mean we talked about Mimas, and the rest are like. Just so much loss, there is so much loss, and it focuses a lot on the treatment of protesters and how horrible that is, and the people are putting their lives on the lines and their bodies to protect something that other, you know, the opposition doesn’t see has any value. And they lose! And I just! Ugh!

Forrest: I know. It’s awful.

Lovis: I mean, I ranted to you about this before and you had a really good comeback. Which I understand, but…still.

Forrest: I don’t disagree with you, though, I should say that. Like, I totally understand where you’re coming from, and I had the same feelings when I was reading the book. And yes, like one of the things that drew me to ecofiction also was this problem of—because I remember like when my sort of understanding of the climate crisis was starting to expand and I was kind of just frantically looking for things to hold on to, to, like, not lose hope. And, yeah, ecofiction was one thing that brought me to that. But a lot of ecofiction is dystopian. It’s not really a happy ending. It kind of starts from the premise of like, “We have failed. Now what?

Lovis: And this is the consequence of our failing.

Forrest: Yes. And here’s all the bad stuff that’s going to happen. So you better change your ways! And it’s kind of like that.

Lovis: Yes. Fear tactic.

Forrest: But yeah, one thing that I was really interested in, I was reading about, like the…I think somebody who works for the UN, I don’t remember who now, but they were talking about the need for narratives in the climate action movement and how important stories, like what a big role stories will play in this. So I was starting to read more about that. And one of the big things was like hopeful stories or like stories that don’t paint such a bleak picture. So all that to say, I don’t necessarily think that The Overstory is a dystopian novel. There are, there’s a very strong counterargument for that statement, as you were saying. But, yeah, it, um, I don’t know, it’s, it’s hopeful in some ways, and it’s very…I don’t know if I should say like pessimistic in other ways and maybe even sort of misanthropic a little bit? But yeah, I think like the, the source of hope from this book that maybe people were talking about is taking the long view. So Richard Powers will talk about, you know, like we need to stop thinking—and it also comes up like when you were talking about Ray and how like the law only looks at like a human timeline, but it needs to look at more of like an ecological timeline. That’s kind of also where Richard Powers is coming from in this book. Like he’s talking about like, um, like we’re only thinking in terms of us as a species, we need to take the long view and think of life on the planet in general. If you look at the whole history of life on this planet, like we’re a very small blip on that little timeline. So maybe it’s kind of conceited of us to think of ourselves as so important, but also like we’re animals, just like every other…animal…on this planet. And we have, like, this instinct for self-preservation and we don’t want to die, obviously! So, yeah, he—I don’t know, it’s all about like, you know, like life comes from death. It’s like the circle of life. And like, even if we go extinct as a species, which like, I think the verdict is still kind of out on whether or not climate change could make that happen. But I mean, regardless, it still would not be a great situation to end up in. But I think where he’s kind of coming from is like, even if, like, everything goes as wrong as it could go wrong, like, life will still find a way to go on, basically. It’s like in Jurassic Park when he’s like, “Life finds a way!” Or whatever. So I think that’s maybe where people are getting the hopeful aspect of this book from?

But also, I think what a lot of people don’t realize is that hope is an act, it’s a verb. It’s not just a philosophy or a viewpoint that you have. It is showing up to protests. It’s planting trees. It’s defying the forces that are seeking to destroy us.

Lovis: Potentially. And you did have a good point that said, the, the point of the purpose of resistance is to resist. I mean, yes, your goal is to win. But it’s not brave if there’s no risk of loss, I suppose.

Forrest: Yeah, exactly.

Lovis: Just the fact that there are people who are standing up for for it and using their voices to speak out against it. That is, that is comforting. If only they would win sometimes!

Forrest: I know. I know. So yeah. I guess I was kind of rambling there a little bit, but. Yeah I guess my main—not rebuttal, but maybe like response to what you were saying—is that. Yeah. Hope is important, and like hope in a lot of times is the only thing that keeps people going when the going gets really hard. And you know, like we’ve heard all these things from people like Elie Wiesel, who was a Holocaust survivor and wrote this book called Night about like how hope is like the only thing that can keep people going. Like if you lose hope, you’ve lost everything, basically. And I think when people hear that, they think like. I guess it’s sort of like faith, like having hope, in a way, is sort of like having faith, like just. “You have to just believe!” And like, you just have to believe that things will be OK in the end and just keep going. And it’s kind of like this discipline, I guess, and a lot of personal rigor in maintaining that viewpoint. But also, I think what a lot of people don’t realize is that hope is an act, it’s a verb. It’s not just a philosophy or a viewpoint that you have. It is like showing up to protest. It’s planting trees. It’s basically just like defying the forces that are seeking to destroy us, I guess, in a word. So that’s where I guess that’s what I kind of feel hopeful about this book was just the courage and the bravery on display from all the characters in the book. Even though they are up against impossible odds, there’s realistically no way they could have won in their situation. And it’s important to also remember that this book, I think, was set in the 90s, at least when all of the big protests were happening with the main characters. So like, again, this was a time when, like, the collective consciousness was not as awake to the climate emergency as it is now, even though it still could be better, like in the 90s. You know, like that’s like when Al Gore came out with An Inconvenient Truth and a lot of people were like, “Oh, this is great!” And then way more people were like, “This guy’s crazy!” So they were just up against impossible odds. But despite that, they fought basically until the end anyway, even though they knew they were probably going to lose. And they just did it because it was the right thing to do and because they had such a strong moral conviction.

The significance of multiple characters and why climate action needs everyone

Lovis: I love that, that hope is a verb. I like that, that you—yes, you can hope for it to get better, but you also need to act for it to get better. And just standing by and and letting it happen in whatever way is decided by the people who do act is good enough. We all need to contribute and you know, we don’t all need to tie ourselves to a tree and get pepper spray in our eyes.

Forrest: And not everybody has the privilege to be able to do something like that too, like not everybody can do that.

Lovis: No, exactly. But I think that’s something else that I really like about all the different storylines is that they all do what they can to try and make something better, even if it’s Ray and Dorothy in their back garden, and just rewilding their garden. That is something that they say in the scope of my life, this is something that I can do. And yeah, Dr. Westerford writes her books and collects her seeds, and Neelay builds his builds his game that he thinks can bring people in. And yeah, the rest of the characters, they do join protests and they are very what we kind of typically think of as activism. They are very active. And they, and they, you know, experience all the horrible responses. Violence and hate and death and, oh, it’s, it’s, it’s awful. And they experience all of it. And so I think, I think that’s something that’s really nice about these storylines. They kind of give you this idea of activism, that there are levels of activism. These little things.

I think that’s something really nice about these storylines. They kind of give you this idea of activism, that there are levels of activism.

Forrest: Yeah. And it kind of just drives home the point that a lot of scientists try to make, which is just like like you were saying, like not everybody has to be out in the streets, like you need, like we need just everybody to be doing what they can do in their own way because there is no silver bullet to stopping something as colossal and horrible as climate change, like it’s going to take a billion different people coming at it from a billion different approaches to really make any kind of meaningful impact. So, yeah, I think that was cool. And I hadn’t really thought of that until you just said that. But yeah, the ways that the the different characters in the end, even though they have been, for all intents and purposes, kind of crushed and defeated, they still find a way to kind of be defiant in their own way.

Lovis: Yeah, they still defy. You see Nick’s art everywhere, and graffiti, and he’s just, you know, speaking the language that he knows and and communicating through art and reminding people, kind of. This is something important. This is, this does affect you. You should get involved.

“The Overstory” ending analysis and our take on “Still”

Forrest: Yeah. And then, of course, we have like his masterpiece, I guess you could say at the end of the book where—this is the biggest spoiler alert, I’m sorry. This is just giving away the entire book. This is the literal last page of the book. But yes, at the very, very end we see him. I think he might be in British Columbia. I can’t remember now. He’s somewhere in the Pacific Northwest and out in the woods, basically, and he’s starting to build this, I guess, like structure that can be seen from the sky. And he’s basically just dragging logs that have fallen to spell out a word and then having a really hard time going at it by himself. And then he meets a Native American man, who, I don’t know how they meet, but…

Lovis: He shows up I think. The guy says I heard there was a crazy man doing something in the woods, and Nick is like, “Yep, that’s me!”

Forrest: Yeah, so Nick is in the woods. And he built this kind of superstructure that you can see from—not from space—but if you’re in a plane probably flying over, you could see it. And it’s just the word “still.” And yeah, I was very perplexed by that ending for a long time, I’ll be honest.

Lovis: It’s kind of anticlimactic, isn’t it?

Forrest: Yeah, I was like, “‘Still?’ What the hell does that mean?” It’s like, are you kidding? That’s how it ends. You had a good interpretation on that that you were telling me, because I was still kind of like trying to make sense of it.

Lovis: Well, I had kind of two, so “still” I mean, just in language “still” has several meanings, like “still” very quiet, something is very still. And I thought that might apply to how trees are just standing very quietly and they’re just growing on their own kind of this is what I do. And they’re just surveying and watching everything happen. And yeah, time is so much slower for them and their lifetime is so much longer. So each bit of time just seems so much less significant. Yeah, they’re just still and they’re just waiting. And we, who are moving at such a faster pace, we’re just kind of. Yeah. We’re just kind of crashing into things. We’re always going. And so I kind of like this idea that, that he was just saying, “Just be still. Learn from trees, and be still.” And then the other interpretation was “still” like “still here.” We’ve spent decades and centuries just cutting down everything so that we can use it and destroying land and all these things and these old growths and these trees are still here, and we can still save them. And we can still turn this around. So there’s a lot of stills that you could use. And I suppose if you look at it that way, then it does end on a slightly hopeful note.

Forrest: Yeah, it’s open to interpretation for sure.

Lovis: Yeah. Like this whole story has been such a crapshoot, but there’s still time and you can still do something. I kind, of I like that interpretation better. There’s still something you can do.

Forrest: It’s like “even still.” Yeah. I thought that was good.

Our favorite aspects of “The Overstory”

Lovis: Yeah, for sure. What was something that you really liked about the book?

Forrest: Well, I did like several things. One, that trees were kind of like characters in the book, so they were sort of like non-human characters, which I think is a powerful thing that you can have in works of ecofiction or just any kind of story you’re trying to tell. It will make the reader more empathetic to what’s going on. Also, the multiple perspectives, the whole cast of characters that we had. One problem that a lot of people have with books about that talk about issues like climate change or just other environmental issues, and one problem that a lot of writers have in trying to write about those issues, is that, at least coming from, I guess, kind of like a Western literature perspective, our stories are a lot of them follow like the hero’s journey, which is, you know, like Lord of the Rings, like Harry Potter, just like those classic, like, epic stories about good versus evil. But it always kind of follows this one character who’s like the main protagonist. He’s like a hero. I’m saying “he” because it’s usually a man, which has its own set of problems as well. So it’s usually not a very inclusive way of looking at a story. It’s also usually kind of dualistic, like there’s good versus evil. There’s not a whole lot of room for nuance. Usually the bad guy dies in the end and it’s like a good thing that the hero killed the bad guy. Yeah, hero wins! Good versus evil. Somebody has to die. So, yeah, it’s like I was saying, there’s not like a ton of room for nuance. And this is not to say that there are not some great stories that have been told using the hero’s journey, because there have been. The two series I just mentioned are pretty great examples of that. But when you’re talking about something like climate change, which is not so simple, it kind of falls apart when you’re trying to do that. So I think that the use of multiple characters and approaching it from like myriad different ways was a very good thing that was working for this book. Trying to think of what else. Yeah, I. I did like and I didn’t like the sort of perspective that he has of we need to take the long view of things and think in more of like epochal terms, I guess, more in terms of centuries than in individual years. Which is great if you’re a tree, but not so great if you’re a human who, you know, like I don’t know what the average life expectancy is like in both of our countries now, but yeah, it’s not a hundred years in most cases. So, yeah, that was one thing that was like OK, like yeah, but. And then yeah. Just like the whole, like we were talking about the whole concept of thinking of nature as something that has intrinsic value. It doesn’t have to be, it doesn’t have to have a potential to be extracted for it to have value. I guess like it’s valuable in its own right, just like humans are.

Lovis: Yeah, for sure, I second everything that you just said. I did, I did like that about, about the book. It has so many facets. It’s really, it’s really—just it is kind of a masterpiece. I mean, there are not that many other books that you can spend an hour and a half talking about them and still not even have talked about half of the things that happen.

Forrest: Maybe some Russian literature.

Lovis: Yeah, yeah. I mean, there’s so much. And I guess, what did I like that you haven’t said? I mean, the writing is one. He’s an absolutely beautiful writer, and I guess this kind of ties in with what you said about the trees becoming characters. That’s, and isn’t it funny that for us to empathize with something we have to make human? But he just—it’s really, it’s not that easy to make a tree a character, and he does it so beautifully and it’s just—it’s a joy to read his writing. And the other thing is that he has put so much information into this book, like real information. Stuff that you can fact check. And you learn something. You learn so much by reading this book and it’s not a book that you will finish and not be impacted by. I think it’s a very impactful book. Of course, the fact that it has so much information and so many stats and so many kind of…just the research he must have done to write this book.

Forrest: He read so many books to write this one. He read like nearly 200 books I think I read.