Stories for Earth relies on contributions from our listeners and readers to produce high quality, in-depth content. If you buy something using the links on our website, we may earn a small commission, at no extra cost to you. For more information, see our Affiliate Disclosure.

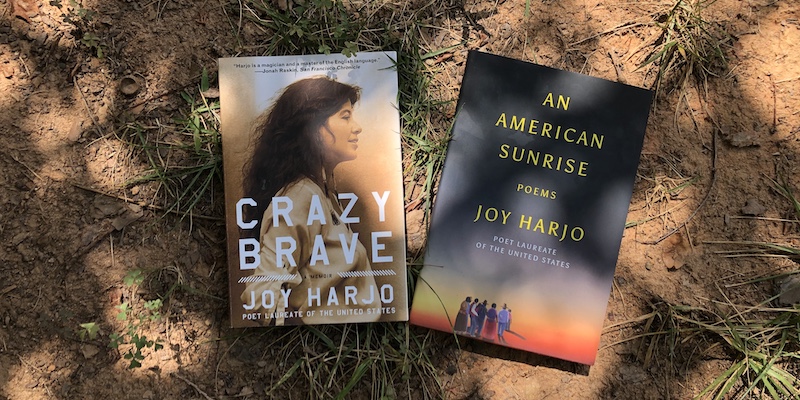

In this episode, we take a deep dive into Crazy Brave and An American Sunrise by US Poet Laureate Joy Harjo. Crazy Brave is Harjo’s 2013 memoir, while An American Sunrise is a poetry collection published in 2019. Both offer invaluable Native American perspectives about humanity’s relationship with the Earth (or lack thereof), how racial injustice and environmental injustice are deeply intertwined, and the need for us to reckon with our past as we look to a brighter future.

Never miss an episode

Subscribe wherever you enjoy podcasts:

Overview

“Crazy Brave”

Crazy Brave is a memoir by US Poet Laureate Joy Harjo of the Muscogee (Creek) Nation. Published by W. W. Norton & Company in 2013, the book details Joy’s life growing up and her path to becoming a poet. Written in Joy’s musical voice and interspersed with moments of deep personal introspection and poetry, Crazy Brave is a memoir that reads like jazz sounds—spontaneous, sublime, and vivacious.

→ Buy on Bookshop from $14.67 (affiliate)

→ Find at your local library

“An American Sunrise”

An American Sunrise is the latest poetry collection from US Poet Laureate Joy Harjo. Published by W. W. Norton & Company in 2019, An American Sunrise grapples with the scarring legacy of the Trail of Tears that saw Cherokee, Muscogee (Creek), Choctaw, and Seminole peoples forcibly removed from their lands in what is now the Southeastern United States. Featuring brief moments of reflection from Harjo, transcripts of interviews with survivors from the Trail of Tears, and Harjo’s masterful poetry, An American Sunrise is a story about the resilience of the Muscogee and other Native tribes against all odds.

→ Buy on Bookshop from $14.67 (affiliate)

→ Find at your local library

Jump to

About Joy Harjo

Joy Harjo is an internationally acclaimed writer and performer of the Muscogee (Creek) Nation. In 2019, she was named the 23rd Poet Laureate of the United States of America—the first Native American person to receive the honor. Joy is the author of multiple poetry collections, a memoir, and several children’s books and plays in addition to being a musical artist with several albums under her belt. The recipient of multiple honors, including the Ruth Lilly Prize, a Guggenheim Fellowship, the Jackson Poetry Prize, the Josephine Miles Poetry Award, the William Carlos Williams Award, and the American Indian Distinguished Achievement in the Arts Award, she lives in Tulsa, Oklahoma.

Official website: https://www.joyharjo.com/

Transcript

Intro

I’m Forrest Brown, and this is Stories for Earth.

[music: “Cold Descent” by Forrest Brown]

Welcome to Stories for Earth, a podcast about everything climate change in pop culture. I’m glad you’re joining us today for the second episode of season two.

For a transcript of today’s show, more information about the author, recommendations for further reading, and links to buy the books that we’ll be talking about today, visit our website at storiesforearth.com. That’s storiesforearth.com.

If you want to support further production of the podcast, you can make a recurring, monthly donation on Patreon at patreon.com/storiesforearth. We have three different tiers to choose from, with perks ranging from things like early access to new content, exclusive episodes of the show, eligibility to perform readings for future episodes, and personal shout-outs. Again, that link is patreon.com/storiesforearth, or you can check out the support page on our website to make a one-time donation.

Today, we’ll be talking about a memoir and poetry collection from US Poet Laureate Joy Harjo of the Muscogee Creek Nation. I hope you enjoy the show today.

Telling stories, banning stories

There are no unsacred places;

there are only sacred places

and desecrated places.

-“How to Be a Poet” by Wendell Berry

When I was a young boy, my mom used to tell me about my great-great grandmother. She had no hair on her arms. Even in her old age, her face showed no wrinkles. She had beautiful, olive skin, and supposedly when she and my great-great grandfather got into it, she would lower herself down into the well until she calmed down. My mom always said she was a “Cherokee princess.” These are the only details I know about my great-great grandmother. Or, thought I knew, until I learned about the myth of the Cherokee princess.

According to Native Languages of the Americas, the myth of having a “Cherokee princess” great-great grandmother is a pernicious one among White Americans. It’s unclear why or how this myth got started, especially since the Cherokee people have never had princesses in their culture. There’s a theory that some indigenous men used a term of endearment for their lovers that roughly translates to the English word “princess.” Another theory states that dubbing a native woman “princess” might have made it more socially acceptable for an interracial relationship between a man of European descent and a native woman. Whatever the reason, the tribe of the princess in question always tends to be Cherokee, regardless of where the myth-spreader is from.

In my case, there is a chance I could have a Cherokee relative, if I do have any American Indian ancestry, but it’s also just as likely for me to have a Creek or Choctaw or Catawba relative. My family are all from the Southeastern United States, at least going as far back as my great-great grandparents, so we’re scattered all over Georgia, Alabama, Tennessee, Florida, and the Carolinas. But that’s beside the point. The point is, at least for many of us White Americans, we have somehow invented a fictitious story about our relationship to the people who called this land home for thousands of years before any European settlers showed up, erroneously thinking they’d found India. From the beginning, we’ve been very wrong about who Native peoples are and about who we are to each other.

The “Cherokee princess” story is a White American story, but for many, many years, it was illegal for Native Americans to share their own stories. From the time it was ratified on March 3, 1819, the Civilization Fund Act attempted to “civilize” American Indians by setting up a fund to help churches work with the government to establish schools for Native children. These schools were eventually set up as boarding schools where children would be sent to unlearn their tribal culture and practices to adopt Christianity and American culture. With many schools established and operated by the Catholic Church, Native children sent to these schools were subject to what has been described as “harsh” and “militaristic” rules and punishments.

Students were not allowed to speak their Native languages, only English. Their long hair—a point of pride for many American Indian cultures—was cut, their families were not allowed to visit them, their tribal religions were banned, and they were often subject to emotional, physical, and sexual abuse. In one account published in The Atlantic, Mary Annette Pember writes about her mother’s experience, who was a student at one such Indian boarding school, as they were called. The nuns at this particular school frequently made students like Pember’s mother scrub the floors for hours, while the nuns called them “dirty Indians.” These and other memories haunted Pember’s mother for decades, up until she passed away.

Pember writes: “Although she died in 2011, I can still see her trying to outrun her invisible demons. She would walk across the floor of our house, sometimes for hours, desperately shaking her head from side to side to keep the persistent awful memories from entering. She would flap and wring her hands over and over again, as though to rid them of a clinging presence.”

The attempt to totally eradicate Indian culture via these boarding schools, a form of ethnic cleansing, thankfully ended in 1978, but the wounds it inflicted left deep scars in surviving Native communities. This is an example of generational trauma, something Native people in North America are tragically all too familiar with. These events and many others should have never happened. They are unspeakable crimes, and as a White man descended from other White men and women who committed such crimes or benefitted from their being committed, I feel deep shame and sadness learning more about them.

But to not learn about and confront this history is to allow it to go on hurting—both the people and the land that was stolen from them, and from which they were eventually driven not long after. This is not a history that affects only one group of people, though it would still demand reckoning if it were. This history affects all of us, and it is directly connected to the extreme destruction of the natural world we are now seeing today. There is no single solution for the United States of America and other “desecrated places” like Canada and Australia to reckon with their long and violent history of persecuting indigenous people, but I think we have a seemingly unlikely gift to help us navigate the road to healing—poetry.

Who is Joy Harjo?

“The power of the victim is a power that will always be reckoned with, one way or the other.”

-Joy Harjo, Crazy Brave

At a reading hosted by UC Berkeley on Earth Day, US Poet Laureate Joy Harjo of the Muscogee Creek Nation, said, “A poem is like an energetic construct made out of words…it will hold what you cannot hold.” Forms of art, like poetry and dancing, are really “forms of medicine,” according to Harjo, and her poetry and music exist as ways for her to process atrocities like the boarding schools created by the Civilization Fund Act and the Trail of Tears, which is a major theme in her latest poetry collection An American Sunrise.

An American Sunrise talks not only about the ongoing trauma to the Indian community from the Trail of Tears, but also of the beauty and resilience of her people and how the current refugee crisis in Central America is another chapter in the Trail of Tears story. In the prologue of American Sunrise, Joy writes:

“There were many trails of tears of tribal nations all over North America of indigenous peoples who were forcibly removed from their homelands by government forces.

“The indigenous peoples who are making their way up from the southern hemisphere are a continuation of the Trail of Tears.

“May we all find the way home.”

According to the Cherokee Historical Association, the Trail of Tears was the “…forced and brutal relocation of approximately 100,000 indigenous people” from many different places in the eastern United States to land west of the Mississippi River, in what is now Oklahoma. In 1830, Congress, under US President Andrew Jackson, passed the Indian Removal Act, which officially started the forced removal of many different Indian tribes from their ancestral lands. These tribes included the Cherokee, Muscogee—or Creek—Chickasaw, Seminole, and Choctaw peoples, over 4,000 of whom died on the Trail from disease, exposure, and starvation. It should be noted that Stories for Earth is currently written, recorded, and produced on unceded Cherokee land.

The Trail of Tears is one of many dark chapters in the history of North America, and the effects it had on American Indians were devastating and lasting—even to modern times. The land the United States stole from indigenous people became a new point of expansion for White settlers, many of whom started plantations worked by enslaved Africans until the end of slavery in 1865.

Plantations and the way by which they operated—slave labor—naturally exhausted Southern soil, leading plantation owners to push further westward in search of new land. And of course, the cash crop for many Southern plantations—cotton—is a very thirsty plant that drains rivers, streams, and aquifers. Not to mention the heavy use of pesticides to defend the plant against harmful pests in more recent times, which in turn releases toxins into the environment and destroys large numbers of insects.

Also read: “Ishmael” by Daniel Quinn, Climate Change, and Moving Beyond a Vision of Doom

From the forced removal of American Indians to chattel slavery to topsoil depletion, the American South is a “desecrated place” indeed, but somehow, throughout all the unimaginable heartbreak, pain, and loss, Joy Harjo sees justice and a returning in the future. In her poem “How to Write a Poem in a Time of War” from An American Sunrise, Joy writes:

Someone has to make it out alive, sang a grandfather

to his grandson, his granddaughter,

as he blew his most powerful song into the hearts of the children.

There it would be hidden from the soldiers,

Who would take them miles, rivers, mountains

from the navel cord place of the origin story.

He knew one day, far day, the grandchildren would return,

generations later over slick highways, constructed over old trails

Through walls of laws meant to hamper or destroy, over stones

bearing libraries of the winds.

He sang us back

to our home place from which we were stolen

in these smoky green hills.

Yes, begin here.

There has yet to be a literal reclaiming of the lands from which American Indians were driven during the Trail of Tears, but I have to wonder—could Joy have been referring to herself when she writes about “the grandchildren?” She writes frequently about her grandfather Monahwee in An American Sunrise, and how she returned to his old home at Okfuskee, near what is now Dadeville, Alabama.

Joy also taught as an English professor at the University of Tennessee Knoxville. Located at the base of the “smoky green hills”—the Smoky Mountains—Knoxville is built on traditional Muscogee land, and Joy talks about how old mounds from Mississippian mound-builder communities still exist on the UT Knoxville campus. To move there from her home in Oklahoma, Joy says she took one of the “most traveled trails” in traditional Muscogee territory, much of which is now covered by Interstate 40. When I lived in Nashville, I used to take I-40 to get to work every morning. Reading these words now, it seems strange to me that I had no knowledge of the road’s history until recently, how it follows a trail some of the indigenous people of this continent built hundreds of years ago.

Whether Joy is writing about herself in this poem or not, it’s difficult to miss this kind of theme in many of the poems contained in this collection, a sort of inevitability that history will come to redeem itself. It reminds me of the famous quote from Martin Luther King, Jr.: “…the arc of the moral universe is long, but it bends toward justice.” And maybe poetry is the way Joy Harjo herself contributes to the bending of this arc. In another poem from An American Sunrise, “For Earth’s Grandsons,” Joy writes:

All through the miles of relentless exile Those who sang the path through massacre All the way to sunrise You will make it through—

Joy has said before that poems are songs. Her ancestors sang songs to their descendants to give them strength. In the same way, Joy’s poems sing to younger Native American generations today, helping them make it through, “all the way to sunrise.”

Joy Harjo’s life

If anyone else wrote about Joy’s experiences, it might sound hopeless or depressing. But the way she writes about it—whether through her poetry, her music, or in her memoir writing—goes to show how truly resilient American Indian peoples are.

Joy was born to an Irish-Cherokee mother and a Muscogee Creek father. In her memoir Crazy Brave, Joy describes her father as a man made tight by the death of his mother and the racist Oklahoma society of the 1950s. While Joy’s mother liked to sing and dance around the kitchen with her newborn daughter, Joy’s father used royalty money from an oil well on family property to support a classic car habit. He wanted a boy, but he still loved Joy and took care of her, even if he did play a little too rough with her sometimes.

Joy’s biological father died of alcoholism when she was still young, and her mother remarried. The man who became Joy’s stepfather seemed good at first, but he turned out to be verbally and physically abusive to Joy, her mother, and her siblings. He forbade Joy’s mother to sing, and he beat her if she ever did anything to upset him, like going out to dinner with her girlfriends or letting Joy go to a friend’s house. Joy eventually fled her parents’ home in high school to attend the Institute of American Indian Arts in Sante Fe, New Mexico where she immersed herself in art, alcohol, drugs, and for one of the first times in her life, meaningful relationships with other Indian children.

After leaving the Institute of American Indian Arts, Joy battled through an abusive marriage that ended in divorce, worked a series of service jobs, and studied pre-med at the University of New Mexico, Albuquerque, eventually switching her major to art. She earned her MFA from the University of Iowa in 1978.

Speaking about her decision to pursue art, Joy writes in Crazy Brave, “I believe that if you do not answer the noise and urgency of your gifts, they will turn on you. Or drag you down with their immense sadness at being abandoned.” Joy Harjo is immensely gifted. She is a writer, a painter, a dancer, and a musician, and she uses these gifts to speak truth to power. In 2019 she became the first Native American to be named the US poet laureate, and she also plays saxophone and flutes in various bands.

But above all else, she is a poet, discovering this about herself after having already faced hardships many people might encounter over a lifetime, if at all. Writing about this discovery, Joy writes in Crazy Brave, “I became aware of an opening within me. In a fast, narrow crack of perception, I knew this is what I was put here to do; I must become the poem, the music, and the dancer.” But to hear Joy talk about writing poetry, it sounds more like a spiritual experience than the honing of a craft. In fact, she talks about the “spirit” of poetry in Crazy Brave, not in the same sense as you might say the “nature of” or the “disposition of” poetry, but as an actual spirit.

She writes: “To imagine the spirit of poetry is much like imagining the shape and size of the knowing. It is a kind of resurrection light; it is the tall ancestor spirit who has been with me since the beginning, or a bear or a hummingbird. It is a hundred horses running the land in a soft mist, or it is a woman undressing for her beloved in firelight. It is none of these things. It is more than everything.”

This kind of openness or connection with something beyond herself is a constant theme throughout Joy’s poetry and memoir work, and I think it’s crucial to her idea of what it means to be a poet. Whereas many writers tend to see themselves as sort of craftsmen or skilled trade workers, I get the impression that Joy Harjo sees the role of the poet as more of a vessel for communication from something beyond our everyday lived experience. The closest words I can think of to describe it is “shaman” or “medium.”

When I read Joy Harjo, I get the sense that she and other poets are here to help us reconnect with each other, with ourselves, and with the planet. Or rather, they are here to help us realize that we already are part of such intricate and beautiful connections, that we are part of nature and that the lines dividing us all up into individuals are perhaps more blurry than we’re conditioned to believe. Even though we might never be able to see the full picture of reality, poets and their poems are cracks in the cave wall of how we perceive the universe.

Indigenous people’s rights are crucial to climate justice

I say that Joy Harjo’s poetry can help us reconnect with the planet because many of us living in developed countries have lost our connection to it. In wealthy, high-tech countries, people enjoy high standards of living, which usually means distancing themselves greatly from nature.

We live in air-conditioned homes with appliances like refrigerators, washing machines, and dryers to reduce manual labor. We buy food wrapped in attractively branded packaging from organized and neatly stocked supermarket shelves. We travel around town sealed off from outside, either in cars, buses, or trains, and for many of us, we spend hours on end each day staring at little lights flashing on a screen.

Joy Harjo writes in her poem from An American Sunrise, “Tobacco Origin Story:”

Flowers of tobacco, or Hece, as the people called it when it called To them. Come here. We were brought To you from those who love you. We will help you. And that’s how it began, way Back, when we knew how to hear the songs of plants And could sing back, like now On paper, with marks like bird feet, but where are Our ears? They have grown to fit Around earbuds, to hear music made for cold Cash, like our beloved smoke Making threaded with addiction and dead words.

We like to think we have conquered the so-called “natural world.” But as Joy Harjo reminds us, to do so means killing ourselves at some point, since we are inseparable parts of nature. This form of suicide may come to industrialized nations unintentionally, but for centuries, colonial powers have been killing indigenous people very much on purpose. Looking back on the age of colonialism, it’s impossible for me to ignore it as the driving force behind our current triple crises of racial injustice, public health, and ecological destruction.

In North America, native peoples were massacred and driven from their lands in the name of European colonists seeking wealth, were repeatedly cheated in broken treaties, and yes, forcibly removed from their land in the name of conservation projects like US national parks. Enslaved people from West Africa were taken from their homes, tortured, maimed, and murdered in forced labor on plantations, and their descendents are still denied basic human rights today. And we now know that humanity’s destruction of nature caused the current coronavirus pandemic, according to leaders from the UN, the WHO, and WWF International. We will continue to cause more disease and illness if we keep on this way.

The colonizer mindsight has royally desecrated our only home, but taking steps toward justice can help us restore the planet. We can start with giving indigenous peoples their land back. This is not only the right thing to do, but research also shows that biodiversity is highest on land managed by indigenous people. At a time when roughly one million species are in danger of going extinct, this could be a double-edged sword doing right by native peoples and the planet.

Indigenous people make up less than five percent of the world population, but they support almost 80 percent of global biodiversity, according to a paper published in Nature. And in a National Geographic article (gated), Jon Waterhouse, an Indigenous Peoples Scholar at the Oregon Health and Science University, said, “Indigenous peoples have mastered the art of living on the Earth without destroying it. They continue to teach and lead by example…We must heed these lessons and take on this challenging task, if we want our grandchildren to have a future.”

The fight continues

In Crazy Brave, Joy Harjo writes, “The power of the victim is a power that will always be reckoned with, one way or the other.” But I’ll be honest—I sometimes have a hard time believing statements like these when I hear them. It could be I’ve grown cynical. It could be I’m still learning about a lot of this dark, heartbreaking history and I’m in a kind of hopeless daze. But Joy is correct here and in her other writings—the path toward justice is not guaranteed to be short. Looking at this cause and many others—the Civil Rights and Black Lives Matter movements of course come to mind—the path is often long and hard. But this doesn’t make it pointless.

For years, Native American activists have been fighting in and out of the courtroom for their rights, and recently, they scored a major win. Earlier this month, on July 6th, Indian Country Today broke the news that a federal judge ordered the shutdown of the Dakota Access Pipeline, requiring that all oil be removed within 30 days of the order. Kolby KickingWoman, who wrote the article, called this a “…huge win for Standing Rock Sioux Tribe, the Cheyenne River Sioux Tribe, and the other plaintiffs.”

Also read: “Beasts of the Southern Wild,” Hurricane Katrina, and Climate Change

Just three days later, NPR reported that the US Supreme Court ruled that almost half of the State of Oklahoma—the land where American Indians were forcibly sent on the Trail of Tears—is Indian land. The article quotes Justice Neil Gorsuch writing in the decision, “Today we are asked whether the land these treaties promised remains an Indian reservation for purposes of federal criminal law. Because Congress has not said otherwise, we hold the government to its word.”

The following Tuesday, on July 14th, the New York Times published an opinion piece by Joy Harjo in which she wrote, “The elders, the Old Ones, always believed that in the end, there would be justice for those who cared for and who had not forgotten the original teachings, rooted in a relationship with the land.” She went on to say, “Justice is sometimes seven generations away, or even more. And it is inevitable.”

At a time when I think many people, including myself, are looking for reasons to be hopeful, to believe that, somehow, the environmental movement will result in justice, these are soothing words to read. It’s understandable that we want to hear these words. Again, I am new to this fight, but people have been fighting environmental and racial justice for decades, for centuries. I don’t want to downplay the significance or the joyfulness of these two major victories, but I also think to end on this note without acknowledging the pain and hard work it took to win them is disrespectful for the people behind them.

Joy doesn’t let us forget this either. She writes in her op-ed about the struggle behind these victories. This is true here in the United States and around the world. Especially in Central and South America, indigenous people are being forced from their land en masse, whether by the violence of drug cartels by logging companies or by government agents. Just as Martin Luther King, Jr. wrote in Letter from the Birmingham Jail, “Injustice anywhere is a threat to justice everywhere. We are caught in an inescapable network of mutuality, tied in a single garment of destiny. Whatever affects one directly, affects all indirectly.”

I said it earlier, and I will say it again: I am an American man of European descent. No matter who my ancestors were or when they arrived here, I have benefited and continue to benefit from the oppression of Native, Black, and other peoples. Reading Joy Harjo has helped open my eyes to the enormous responsibility I have to help right the wrongs of the past and to fight for justice and reparations. If you are listening to this now as a person of similar privilege, I ask you to do the same. Part of this involves seeking out voices like Joy Harjo’s and listening intently to all they can teach us, but there is so much more work to do, even more than can be achieved in a lifetime. This will be long, hard work, and those of us alive today will probably not live to see the end of it. Maybe we will. What matters is that we keep at it—that’s the only way justice will ever be achieved.

Recommendations for further reading

Poetry collection: Conflict Resolution for Holy Beings by Joy Harjo

→ Buy on Bookshop from $14.67 (affiliate)

→ Find at your local library

Book: Braiding Sweetgrass by Robin Wall Kimmerer

→ Buy on Bookshop from $16.56 (affiliate)

→ Find at your local library

Book: An Indigenous Peoples’ History of the United States by Roxanne Dunbar-Ortiz

→ Buy on Bookshop from $14.72 (affiliate)

→ Find at your local library

Book: There There by Tommy Orange

→ Buy on Bookshop from $14.72 (affiliate)

→ Find at your local library