Stories for Earth relies on contributions from our listeners and readers to produce high quality, in-depth content. If you buy something using the links on our website, we may earn a small commission, at no extra cost to you. For more information, see our Affiliate Disclosure.

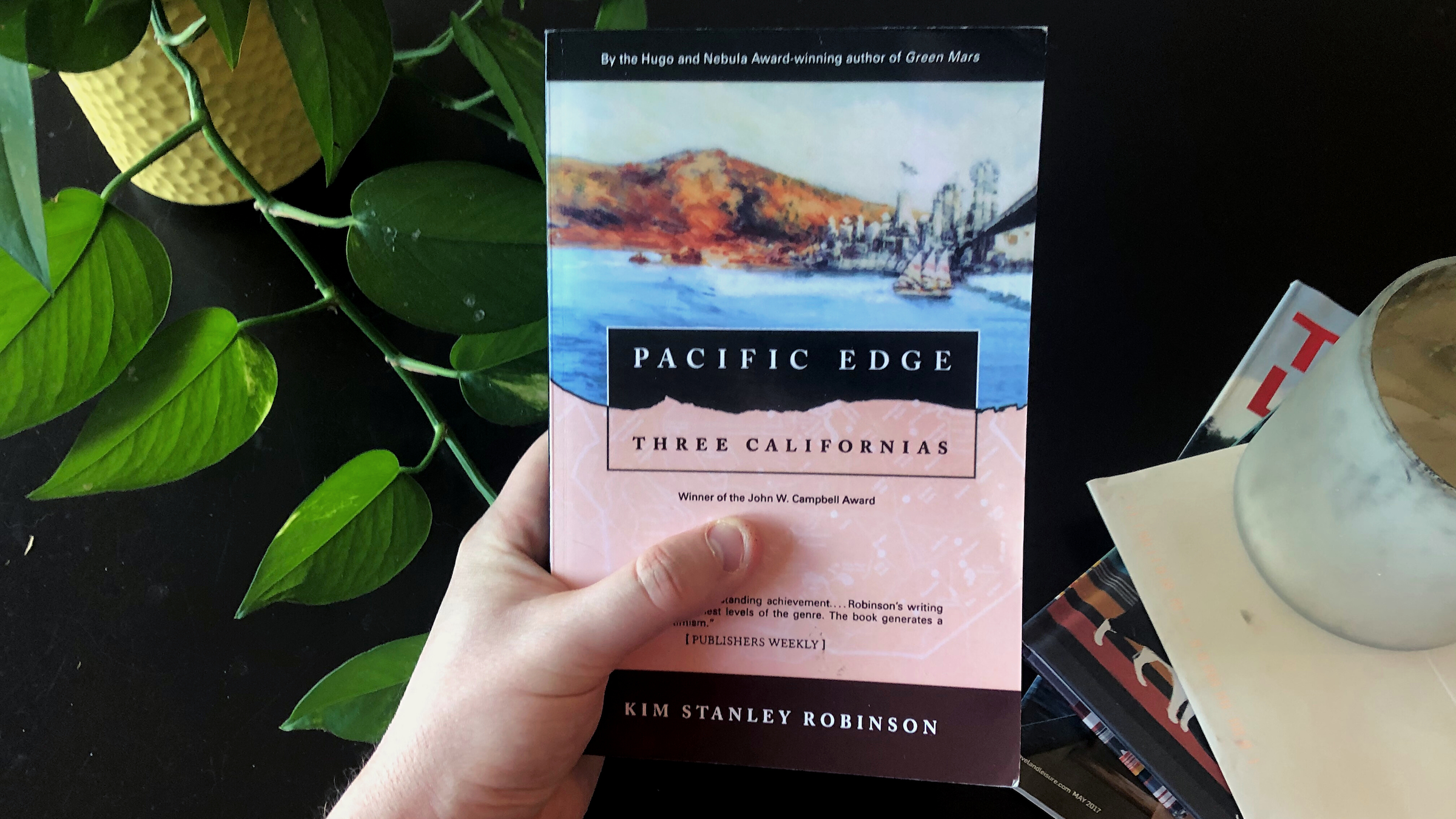

Kim Stanley Robinson’s 1990 classic Pacific Edge is an inspiring vision of how we might create a truly sustainable society. Part of a three part series—or triptych—the novel presents a utopian or solarpunk imagining of Orange County, California in the 2060s, telling the story of Kevin Claiborne as he and his friends attempt to stop an ecologically destructive zoning proposal on one of the last pristine hillsides in their neighborhood of El Modena.

Never miss an episode

Subscribe wherever you enjoy podcasts:

Overview

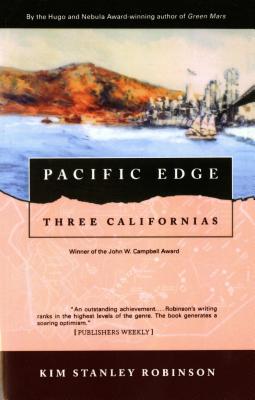

Pacific Edge by Kim Stanley Robinson (buy on Bookshop from $22.07) is a work of utopian eco-fiction set in Orange County, California during the 2060s. Originally published in 1990 as part of the Three Californias triptych, Pacific Edge includes many solarpunk themes such as energy independence through renewables, flourishing of local communities, green infrastructure and high technology, and strict government regulations limiting the power and size of corporations. The other two books in the triptych depict alternate futures for California—one struggling through a nuclear winter (The Wild Shore) and one being crushed by extreme wealth inequality caused by a giant tech boom (The Gold Coast). Pacific Edge takes a different route, using utopia as the setting with the still-fresh memory of a past dystopia threatening to return.

→ Buy on Bookshop from $22.07 (affiliate)

Jump to

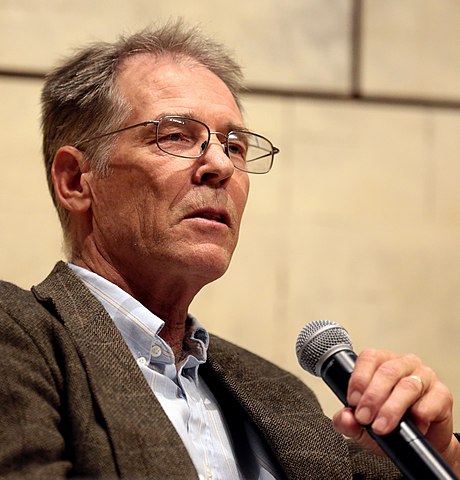

About the creator

Kim Stanley Robinson is a literary science fiction writer from Davis, California. Born in Waukegan, Illinois in 1952, Robinson moved to Southern California as a child but has also lived in Washington, D.C. and Switzerland. His books frequently incorporate themes of climate change, sustainability, nature, environmental justice, and critiques of capitalism. The author of over 19 books and numerous short stories, Robinson has been awarded the Hugo, Nebula, and Arthur C. Clarke Awards for his literary contributions to science fiction. He holds a BA in literature from UC San Diego, an MA in English from Boston University, and a PhD in English from UC San Diego, and he has taught at UC Davis and the Clarion Science Fiction and Fantasy Writers’ Workshop. His new novel The Ministry for the Future will be published in fall 2020.

Official website: https://www.kimstanleyrobinson.info/

Transcript

I’m Forrest Brown, and you’re listening to Stories for Earth.

[music: “Cold Descent” by Forrest Brown]

Welcome to Stories for Earth, a climate change podcast where we discuss stories that can give us strength and resilience in fighting the climate crisis. I’m glad you’re joining us today for the last episode of our first season.

For a transcript of today’s show, more information about the author, recommendations for further reading, and links to buy the book that we’ll be talking about today, visit our website at storiesforearth.com. That’s storiesforearth.com.

Today, we’ll be building off our discussion from last month by talking about Kim Stanley Robinson’s 1990 science fiction novel Pacific Edge, part of the Three Californias triptych. If you don’t like spoilers, now would be the time to turn off the podcast, read the book, and come back to finish the episode when you’re done.

But whatever order you decide to do things in, I hope you enjoy the show today.

“Pacific Edge” plot summary

I want you to imagine that you live in Southern California, in Orange County. Maybe you already do. The year is 2065, and apart from the time difference, most of your story could be happening today. Your job is renovating old houses. You have just won an election to serve in the local government. You’re in your early thirties, and you are in love for the first time.

The subject of your infatuation just separated from their partner of 15 years. Until now, you thought they’d only seen you as a friend. But now after the breakup, things are different. They start approaching you, wanting to spend time with you, inviting you on solo walks and flights around the county. The two of you begin to fall in love, and, for a while, life is good. It almost seems too good.

You see, your lover’s ex just so happens to be the town’s mayor and the CEO of a highly successful medical technology company. Shortly after you begin your term as an elected official, the mayor proposes rezoning a parcel of land that’s set aside for a park. They want to use the land to build a new commercial building for their company, even though your political party has worked hard for years to protect the land and leave it as wilderness. Oh, and the land is the hill that’s practically in your backyard.

Obviously, you want to fight this proposal, but think of how it will look considering you’re sleeping with the mayor’s recent ex-lover. And speaking of which, think, too, about the way this will look to your lover. Will they think you’re simply trying to rub it in the mayor’s face? Will they resent you for fighting against the zoning proposal with everything you’ve got? This is a tricky situation, and to get what you want, you’ll have to navigate it carefully, all while trying to act naturally. You’re angry, frustrated, and torn. Don’t you live in a beautiful place? Aren’t you surrounded by friends? Isn’t this supposed to be a utopia?

This is the plot of Kim Stanley Robinson’s novel Pacific Edge. Originally published in 1990—two years before Daniel Quinn told us we need to move beyond a “vision of doom”—Pacific Edge is a work of utopian ecological fiction that paints a portrait of what Southern California could look like if humans take swift and appropriate action to mitigate and adapt to climate change. The book is part of a triptych—a picture in three parts—that offers ideas about three different possible futures for California. One book depicts a future California struggling through a nuclear winter, another depicts a technocratic future marked by extreme income inequality, and the third, Pacific Edge, shows a hopeful future, one where humans have learned to live in harmony with the environment, limit growth, and work on restoring places wrecked by years of overdevelopment, overconsumption, and overpopulation.

At this point, it might be helpful for you to go back and listen to our previous episode on Ishmael by Daniel Quinn. You can still get something meaningful from today’s discussion without knowing about Ishmael, but I think Pacific Edge seems much more timely and important when discussed with Ishmael fresh in your memory. You can take this opportunity to press pause and come back to this episode, or continue listening to hear about Kim Stanley Robinson’s utopia.

There is no such thing as a pocket utopia

The word “utopia” comes to us from Sir Thomas Moore, who created the word for his 1516 book of the same name by joining together two Greek words: ou, meaning “not,” and topos, meaning “place.” By definition, utopias are nowhere to be found. They do not exist. Intended to be a fictional imagination of a perfect world, the very word implies their impossibility. We live in a flawed world full of flawed people; a utopia can never exist.

But even though Wikipedia wasn’t a few keystrokes away in the late 80s, Kim Stanley Robinson was wise to this bit of knowledge when he wrote Pacific Edge. As we discover throughout the book, one of the main characters, Tom, wanted to write a utopia but found it impossible. A constant refrain marks his journal entries: “There is no such thing as a pocket utopia.” A pocket utopia. A small-scale, or island utopia, much like the very first imagining of such a place from Thomas Moore. But what about a utopia on a wider scale? Could that be possible?

The problem with utopias is that—so far, at least—they have all descended into dystopia, the exact opposite of what is supposed to be a perfect place. It turns out that not all visions of a perfect world are the same, and what may be heaven for one group of people is hell for another. Consider Communism in the 20th century. This was supposed to be a perfect society. It was supposed to fix all the problems caused by capitalism over the centuries before. But of course, we all know how that ended.

In China, the Cultural Revolution was an absolute disaster that killed millions of innocent people. In Russia, the rise of Vladimir Lenin and Joseph Stalin resulted in widespread killings, starvation, and poverty. By all accounts, Communism was an absolute failure. It might be the best modern example of why utopias are such a bad idea.

So why write a fictional utopia? Why read a fictional utopia? As I’ve already hinted at, Kim Stanley Robinson did his homework on utopias, and he didn’t fall for the same pitfalls that writers before him did. At worst, utopias kill people—as in Communist China and Soviet Russia—and at best, they’re just plain boring, as in the work of utopian fiction Island by Aldous Huxley. If everything is perfect, what is there to do? There can be nothing to work towards, nothing to fix, nothing to solve, nothing to improve, no conflict of any kind. While at first this may sound great, it begins to sound more and more like a definition of death. I don’t think anyone truly wants to live in a world like this.

But the vision of utopia that Robinson presents in Pacific Edge leans more into the “no place” meaning of the word than the “perfect place” meaning. This is a subtle but important distinction. Pacific Edge doesn’t make any pretenses about being able to achieve utopia; rather, it acknowledges that utopia is never an attainment but a striving. In a journal entry at the beginning of Chapter Four Tom writes:

“What a cheat utopias are, no wonder people hate them. Engineer some fresh start, an island, a new continent, dispossess them, give them a new planet sure! So they don’t have to deal with our history. Ever since More [sic] they’ve been doing it: rupture, clean cut, fresh start.

“So the utopias in books are pocket utopias too. Ahistorical, static, why should we read them? They don’t speak to us trapped in this world as we are, we look at them in the same way we look at the pretty inside of a paperweight, snow drifting down, so what? It may be nice but we’re stuck here and no one’s going to give us a fresh start, we have to deal with history as it stands, no freer than a wedge in a crack.

Stuck in history like a wedge in a crack With no way out and no way back— Split the world!

“Must redefine utopia. It isn’t the perfect end-product of our wishes, define it so and it deserves the scorn of those who sneer when they hear the word. No. Utopia is the process of making a better world, the name for one path history can take, a dynamic, tumultuous, agonizing process, with no end. Struggle forever.

“Compare it to the present course of history. If you can.”

In Kim Stanley Robinson’s imagining of utopia, it must be ecumenical. And I use that word intentionally.

Ursula K. Le Guin—another utopian science fiction luminary and a huge influence of KSR’s who actually got a call out in the preceding quote—wrote many novels that took place in something she called the Ekumen. The Ekumen is a peaceful confederation of different planets that all work together for the advancement of humanity and the expanding of consciousness. We see a similar vision of this kind of utopian framework in Carl Sagan’s 1985 science fiction novel Contact. After receiving a series of extraterrestrial transmissions containing the blueprints for a vessel of interstellar travel, a group of scientists from Earth voyage to the center of the galaxy to meet representatives from alien races. The reason behind this meeting turns out to be for nothing other than sharing knowledge in the hopes of making every conscious being better off.

And this is where Pacific Edge truly shines: it gets at a similar kind of utopian society, although Earthbound. In order for humans to make any progress towards utopia, we must widen the scope of who and what we count as stakeholders. Call this society what you will—ecotopia, the Ekumen, the space station at the center of the Milky Way, the Kingdom of God, Earthseed—every one of them emphasizes embracing all living creatures and nature while working under the assumption that there is no one “right way” to live, as Daniel Quinn insists in Ishmael. “There is no such thing as a pocket utopia.” If a very small fraction of us live in palaces built on the rest of the world’s back, we have not achieved utopia.

A practical utopia

Talk about utopia seems to always bend towards the philosophical. And while philosophy is important, we’ll never make any progress in our journey towards utopia without also discussing the practical. In this regard, Pacific Edge walks and chews gum at the same time. The journal entries from Tom supply the philosophical context for why the world needs a utopian work of fiction, and the story of Kevin fighting the new zoning proposal provides the actual boots-on-the-ground examples of what striving for a utopia looks like. We can, in other words, work on building a utopia while we’re still trying to figure out just what exactly that means.

The story focuses mainly on Kevin’s attempts to thwart the mayor, Alfredo, from building a massive development on the hill behind Kevin’s house, but to me, Tom is the most interesting character in the book. Tom is Kevin’s grandfather and a retired lawyer, and while we don’t find out until later on that he wrote the journal entries preceding many chapters, Kevin does let us know from the beginning that Tom played a very important role in helping their town make good progress on reducing its carbon footprint. In fact, as the story goes on, we learn that Tom was a key lawyer in drafting many of the laws that put international limits on the size of corporations, the populations of towns and cities, and the amount of excess water that communities can store.

But Tom didn’t start out so successful. At the beginning of Chapter Two when we read his first journal entry, we learn that he’s living in Zürich, Switzerland in the 2010s while his wife works on her PhD. A so-called “pocket utopia” itself, Switzerland’s society is really starting to feel the pressure from the sudden and massive influx of refugees from natural disasters and armed conflicts around the world. Of course, these are all side effects of climate change, as Tom notes that the world’s climate has increased another degree Celsius above the pre-industrial average and that more and more species are going extinct every year.

All of this combined is causing a rise in Swiss nationalism and far-right politics. “Return Switzerland to the Swiss!” becomes a common chant, and soon Tom and his wife get a letter from the Fremdenkontrolle der Stadt Zürich—The Stranger Control—which results in Tom’s deportation back to the United States. But even after he arrives home, Tom is greeted with hostility from the American government. Classified as a radical anti-capitalist (and therefore anti-American), Tom is imprisoned and quarantined after a federal immigration agency fabricates HIV-positive test results for him.

Writing some of his later journal entries from prison, Tom scraps his ideas to write a utopia and rededicates himself to fighting for a better future on the same front from before his time in Switzerland—the legal system. After decades of hard-won legal battles, Tom emerges as the leader of the newly formed Green Party and leads America and the rest of the world in mitigating the worst effects of climate change and putting adaptation strategies into place.

Tom effectively helped save the world, so when Alfredo, the town’s mayor, tries to build on Kevin’s hill, Tom joins Kevin in trying to stop the proposal from passing. At the end of the book after Kevin and his friends fail to stop Alfredo, it’s Tom who finally manages to save the hill once and for all. Tom dies in a shipwreck right before Alfredo starts construction, and the town council votes to turn the hill into a memorial for Tom. This halts not only this one development but all future developments from destroying the delicate ecosystem on Kevin’s hill. The situation seemed very grim, but the characters fought tirelessly against regressing. It’s a hard-earned victory, but they win nevertheless.

A positive self-fulfilling prophecy

You probably already know where I’m going with this. We are, right now, in the same position Tom was in when he decided to stop writing his utopian novel. In Europe, the Syrian refugee crisis prompted a bolstering and resurgence of nationalism, xenophobia, and outright Nazism, in some cases, with the rise of parties like the National Rally party in France and the Alternative for Germany (AfD) party. Here in the United States, Central American refugees are traveling up through Mexico to seek asylum in our country, something many Americans have shamefully chosen to use as fuel to throw on the fires of nationalism and racism. Whether they’re chanting “America First” or “Blood and Soil,” it all boils down to the same thing.

Within the past ten years, far-right, populist politics have swelled in popularity, the world’s climate has continued on a terrifying heating trend, the oceans have become hotter and more acidic, and more and more species have passed under the crosshairs of extinction. We live in a fraught time, and our actions today and every day have a huge impact on what the world will look like in ten and twenty years, but also in one, two, and five years since we are now experiencing very dangerous effects of global climate change.

In such a time, becoming overwhelmed and hopeless is the status quo, but we must buckle down and fight this feeling if we want to save our future. We hear frightening stories of dystopia all the time that confirm our worst fears about what the future will be like. We devour books like The Handmaid’s Tale and The Hunger Games with a rapacious appetite, but what if we dared to dream of something better, something that looks more like a utopia? Sure, the bad guys never win at the end of these books. If they did, no one would read them. But these stories always begin in a world where the bad guys have already won. It’s up to the heroes to restore justice and goodness to the world.

What if, instead, we set our sights on a future where the good guys won and the bad guys are the very last of a dying breed. I am usually one to shy away from what could turn out to be self-fulfilling prophecies, but in this situation, I think a positive self-fulfilling prophecy could do us all a lot of good. The characters in Pacific Edge may be fictional, but they are a perfect representation of this idea. Tom found the drive to create the future he envisioned only because he thought it was possible, only because he’d already imagined how that future would be.

If it weren’t for Tom and the hundreds if not thousands of other people who fought alongside him, Kevin wouldn’t have even been thrown into a situation where he had to push back against something as seemingly inconsequential as a new zoning proposal. Kevin’s world might still be imperfect to him, but to us reading about it today, it seems closer to utopia than anything else we’ve seen, and that gives us something to work with.

Tom teaches us that now is not the time for despair. Nor is it the time to give up. Now is the time to work our asses off.

[music: “Cold Descent” by Forrest Brown]

Stories for Earth is written and produced by me, Forrest Brown. The intro and outro music is also by me. If you want to learn more about what we’re up to, you can find us on Instagram at @storiesforearth and on Twitter at @stories4earth. That’s the word “stories,” the number “4,” and the word “earth.” Our website is storiesforearth.com, where you can also find links to support us financially through Patreon and through our Bookshop.org page.

Thank you so much for joining us on our first season. Things will be quiet over here for a couple of months as my wife, our cat, and I get ready to move across the country from Nashville, Tennessee to Portland, Oregon, but we’ll be back very soon with more stories that can give us strength to fight climate change. Until then, thanks for listening.

Recommendations

Book: Always Coming Home by Ursula K. Le Guin

→ Buy on Bookshop from $31.50 (affiliate)

Article: “A Sci-Fi Author’s Boldest Vision of Climate Change: Surviving It” by Russell Gold in the Wall Street Journal (paywall)

Book: Solarpunk: Ecological and Fantastical Stories in a Sustainable World by Fabio Fernandes, Gerson Lodi-Ribeiro, and Carlos Orsi

→ Buy on Bookshop from $13.75 (affiliate)

Book: Ecotopia by Ernest Callenbach

→ Buy on Bookshop from $12.88 (affiliate)