Stories for Earth relies on contributions from our listeners and readers to produce high quality, in-depth content. If you buy something using the links on our website, we may earn a small commission, at no extra cost to you. For more information, see our Affiliate Disclosure.

Overview

Beasts of the Southern Wild is a 2012 film from director Benh Zeitlin and Court 13 Arts. Originally released in New York and Los Angeles, the film was later sold to Fox Searchlight Pictures and distributed worldwide. The film enjoyed mostly positive reviews from critics and viewers alike, and it features an Oscar-nominated performance from Quvenzhané Wallis, who played Hushpuppy. Director Benh Zeitlin co-wrote the screenplay with his screenwriter friend Lucy Alibar, basing the movie on Alibar’s play Juicy and Delicious.

Jump to

About the creator

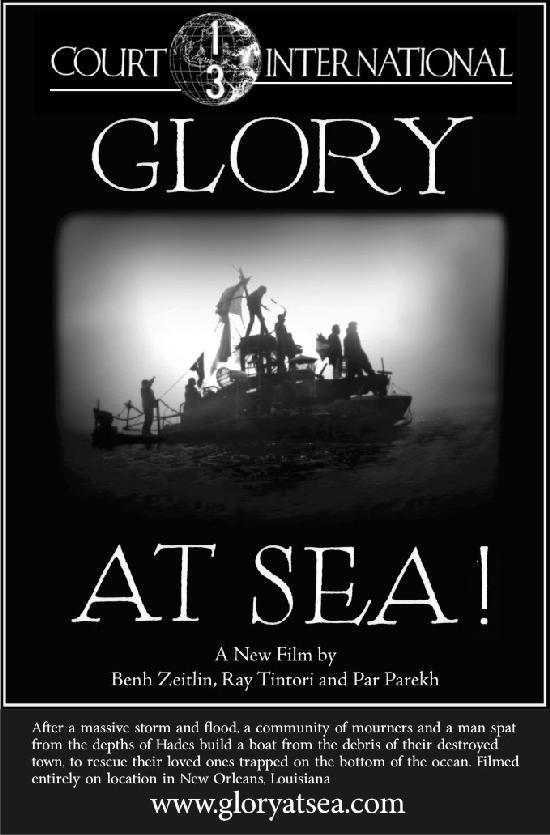

Benh Zeitlin is an American writer, director, and composer who is best known for his 2012 film Beasts of the Southern Wild. Born in New York City and raised in various boroughs and suburbs, Zeitlin is a graduate of Wesleyan University in Connecticut and a co-founder of Court 13 Arts, a “…film and multi-disciplinary arts organization” that works to advance filmmaking in New Orleans, Louisiana. Zeitlin co-founded Court 13 shortly after moving to New Orleans in 2008 to make his first short film, Glory at Sea. In October 2019, Zeitlin revealed work on his next feature-length film Wendy, a modern adaptation of Peter Pan by J.M. Barrie.

Transcript

I’m Forrest Brown, and you’re listening to Stories for Earth.

[music: “Cold Descent” by Forrest Brown]

Welcome to Stories for Earth, a climate change podcast about stories that can teach us lessons of resilience for fighting the climate crisis. For a transcript of today’s show, further recommended reading and viewing, articles, and more, visit our website at storiesforearth.com. We’re on Instagram and Twitter, and you can also support our show via Patreon with a recurring, monthly donation. Click “support us on Patreon” from our website, or visit patreon.com/storiesforearth to become a patron.

Today’s show is about the film Beasts of the Southern Wild. Don’t worry if you haven’t seen the movie before, as I’ll tell you everything you need to know about it for our discussion. If you’d rather find out for yourself, stop the podcast right now, go watch the movie, and come back when you’re done. There are lots of spoilers ahead.

Regardless of whether you’ve seen the movie or not, I hope you enjoy today’s show.

“Beasts of the Southern Wild” plot summary

Beasts of the Southern Wild is the story of Hushpuppy, a little girl who lives with her father Wink in a fictional southern Louisiana town called the Bathtub. The Bathtub is a sort of utopian anarchy. It’s a secluded and wild place on the frontlines of sea level rise, separated from the rest of civilization by a massive levee that holds back the encroaching salt water.

The people who live there are whimsical and free, and they all take care of each other for the greater good of the community. Hushpuppy lives with Wink in a trailer home on stilts, and when she’s not at school, she spends her time playing in the woods around their house and learning lessons from Wink.

Wink seems like a bad father at first. In fact, many viewers might think he’s abusive. He threatens, screams, and shouts at Hushpuppy, and he lets them both live in nothing short of squalor. But Wink loves Hushpuppy more than anything, and he’s hard on her because he’s afraid he won’t be around for long. He wants to prepare her for life.

The movie never says what it is, but Wink seems to have some sort of heart problem that causes him a lot of pain and even makes him pass out from time to time. He’s worried about what will happen to Hushpuppy when he dies, and he especially wants to train her for what Hushpuppy calls “the Big One.”

The Big One is a powerful storm that will bring about the end of the world. Hushpuppy describes it best:

“One day, the storm’s gonna blow, the ground’s gonna sink and the water’s gonna rise up so high ain’t gonna be no Bathtub, just a whole bunch of water…But me and my daddy, we stay right here. We is who the earth is for.”

And the Big One definitely comes. One night, Hushpuppy and Wink get into a fight, and Hushpuppy hits Wink in the chest. This seems to trigger Wink’s heart condition, and he collapses on the ground, appearing to be dead. But something else happens here. We see shots of Arctic ice sheets breaking off into the ocean, unleashing ancient pig-like beasts called aurochs and sending the Big One. Wink regains consciousness just before the storm hits and gets Hushpuppy to safety, but not everyone is so lucky.

In the morning, once the storm has subsided, Wink and Hushpuppy survey the flood damage from their makeshift boat made of an old truck bed with an outboard motor. The survivors soon discover that the salty flood water has contaminated the Bathtub’s fresh water, so Wink and a few other men hatch a plan to blow up the levee separating the Bathtub from the mainland.

Wink and his friends build a pipe bomb and successfully destroy the levee, draining the Bathtub just before FEMA comes to force everyone to evacuate to a hospital on the mainland. The hospital represents everything the Bathtub isn’t, and the Bathtub survivors have a hard time trying to adapt. Wink gets surgery to try to fix his heart condition, but at the first chance, he breaks out and frees the others so they can escape.

Once they arrive back in the Bathtub, Hushpuppy must confront the aurochs before they trample over everything. She’s brave and defiant, and she tells the aurochs, “I have to look after my own.” They seem to understand her somehow, and they turn around to leave. This fulfills something Hushpuppy said earlier in the movie:

“Everybody loses the thing that made them. It’s even how it’s supposed to be in nature. The brave men stay and watch it happen, they don’t run.”

Wink dies shortly before the aurochs leave, and Hushpuppy lights his funeral pyre. In one of the final scenes, we see Hushpuppy marching down the beach in a sort of rag-tag parade with the other residents of the Bathtub, boldly meeting her future and reclaiming her home.

Making the film

Beasts of the Southern Wild was not made the way most Hollywood films are made. Director Benh Zeitlin and his production studio, Court 13, made the entire movie in a southern Louisiana town called Montegut, of the quickly eroding Terrebonne Parish. Court 13 worked out of an abandoned gas station throughout production of the film, and they built all the sets for the Bathtub using found materials in the area. I don’t know if it gets more authentic than that.

Zeitlin calls Court 13’s approach to filmmaking “community-based,” and he uses words like “utopia” when describing how they work together. This way of creating collaboratively worked better in New Orleans than in any other city, according to Zeitlin, which makes sense to me based off what I think I know about New Orleans. I’ve unfortunately never been.

When I watched interviews with members of Court 13 to prepare for this episode, I got the sense that they were just as much a crew of pirates as they were a crew of filmmakers. They seemed totally immersed in the process, but they’re hardly the only ones.

None of the actors you see in the movie were professionals—they’re real members of the community in Louisiana, which actually makes them better than professionals. Dwight Henry owned a bakery in New Orleans before playing the role of Wink, and the unforgettable Quvenzhané Wallis was only five years old when she auditioned to play Hushpuppy. Five years old! She went on to be nominated for the Academy Award for Best Actress after the film’s release, making her the youngest person ever to be nominated in that category.

Beasts of the Southern Wild blew audiences and critics away all over the world, and it’s easy to see why. The people who tell the story of the Bathtub aren’t some actors from out of state. They actually lived the story of the movie. They know what it’s like to go on the roof to escape hurricane flood waters. They knew what it was like to almost have their home completely annihilated yet choose to rebuild it and stay anyway.

Above all else, this film is a love letter to the joyful, resilient people of southern Louisiana and to the home they hold so dear. And just like Hushpuppy loved her dying father and refused to give up on him, these people love where they’re from even while the ocean slowly takes it back.

“Beasts of the Southern Wild” and Hurricane Katrina

You can’t talk about Beasts of the Southern Wild and not talk about Hurricane Katrina. The film is a response to the hurricane, particularly to the way people from outside of the affected area reacted to it. Director Benh Zeitlin said it himself in one interview I watched, talking about the reactions he’d hear from people who couldn’t believe residents of New Orleans would want to move back. I remember hearing these takes too.

People would say things like, “That’s what you get when you build a city below sea level.” It was like they were blaming the people of New Orleans for what happened to them. “Of course your city was destroyed,” these people seemed to say. “You people were dumb enough to put it right in front of a hurricane.”

Zeitlin left this out of his interview, but I heard much worse reactions. Perhaps you did too if you ever watched any Fox News around this time. A lot of the Christians in my life growing up tried to compare the destruction of New Orleans to the destruction of Sodom and Gomorrah in the Bible. This is the story from the book of Genesis, chapters 18 and 19 in the Old Testament in which God destroys the ancient cities of Sodom and Gomorrah with fire and brimstone because the cities were so wicked. Abraham, an Old Testament patriarch, begged God not to destroy the cities if he was able to find even ten good people there. God agreed to Abraham’s terms, but he still sent two angels to the cities to destroy them in the end.

Abraham lived elsewhere, so God sent the two angels to warn Abraham’s nephew Lot to evacuate along with his wife and daughters. God was so mad at Sodom and Gomorrah that he even instructed Lot and his family not to look back as it was being destroyed. Lot’s wife famously looked back anyway, and God turned her into a pillar of salt for her disobedience.

It was the same situation with New Orleans, supposedly. A girl I went to school with even told me about her dad, a preacher, who spent an entire sermon series talking about why New Orleans got what was coming to them. To this day, I don’t really know what exactly New Orleans was supposed to have done wrong. Was it the voodoo? The large queer community? The partying and gambling on Bourbon Street? I honestly don’t really care to hear about it.

But Beasts of the Southern Wild is a direct rebuttal to that line of thinking, in my mind. The Big One or God or climate change or whatever you want to call it destroys the Bath Tub, and what does Hushpuppy do? She looks back. Hell, she goes back—everyone does, including the dying Wink. Their home was already destroyed by the hurricane, and even with the aurochs on their way, the people of the Bath Tub go back. Why? It has everything to do with love and with standing up for what’s right.

Throughout the movie, Wink’s health gradually deteriorates. From the beginning of the movie when we first see evidence of his heart condition, we can tell his days are numbered. But does Hushpuppy give up on him? No. They have a tumultuous, even traumatizing relationship as father and daughter, but Hushpuppy still doesn’t leave him. For the characters in the movie, Wink is a symbol of the Bath Tub—both he and the Bath Tub are dying. One has a heart condition and one is slowly drowning. But this is no reason to give up on them. Even as Wink’s funeral pyre goes up in flames and the Bath Tub lies in ruins, Hushpuppy confronts the aurochs to defend her people. For her, it’s not a question. Wink was her father and the Bath Tub is her home. For Hushpuppy, it’s simply the right thing to do. “The brave men stay and watch it happen, they don’t run.”

It’s the same story for the people of New Orleans and southern Louisiana in general. They didn’t give up on their home just because a hurricane tried to blow it away. A lot of the people who were lucky enough to evacuate, maybe most of them, went back. I’ve heard people describe the ones who didn’t go back as some of the first climate refugees in America. But those who did go back helped rebuild their city, and today, New Orleans is doing okay.

Climate change is making hurricanes stronger

That isn’t to say recovering from Katrina was easy by any stretch of the imagination. In 2010, a group of researchers from Princeton University, Washington State University, the University of Massachusetts in Boston, and Harvard University published a paper about the long term mental health effects of Hurricane Katrina on 532 low-income mothers in the New Orleans area. The researchers started surveying people in 2003, two years before the storm hit in August 2005, and they followed the same people for nearly five years after the hurricane.

And what did they find? The mothers’ mental health never really returned to baseline. In other words, after Hurricane Katrina, these people were never the same. Four years after the storm, about 33 percent of the mothers still showed signs of post-traumatic stress disorder, and another 30 percent suffered from psychological distress. While the researchers saw the worst effects on mental health during the first 11 months after the hurricane, many more people suffered for years afterward.

These people had lost their homes and loved ones, and they had to go for stretches of time without knowing if they would have food or clean water. They were also scattered across 23 states immediately after the hurricane. They were refugees—of course their mental health suffered. But studies like this one are sadly rare.

The researchers who published this paper got kind of lucky. Their paper started out as a study of low-income adults enrolled in community colleges around the US. It just so happened that three of those colleges were in New Orleans, and the researchers had the good sense to draw the study out even longer to fill a knowledge gap in what we know about the mental health impacts of natural disasters.

Hurricane Katrina was just one storm. Imagine how other natural disasters around the world might be affecting people there. I think back to March 2011 when a horrible earthquake and tsunami killed hundreds of people in Japan and nearly caused a nuclear meltdown. As recently as October 2019, a typhoon hit the very same region, testing Japan’s resilience and recovery progress over the past eight years.

A month before this typhoon hit Japan, Hurricane Dorian hit the Bahamas as a category 5 storm—the strongest category designation for hurricanes. The storm essentially sat on the country for three days, killing 70 people and causing nearly 300 people to go missing. The total cost of this disaster tallied up to $3.4 billion USD. For a country with a GDP of about $12 billion USD, this is an unfathomable cost to rebuild.

According to Yale Climate Connections, the verdict is still out on whether or not climate change will cause more hurricanes, typhoons, and cyclones. But for now, scientists feel confident that climate change will make hurricanes that send more rain and cause more destruction. These storms will be beastly—pun intended—and we should be putting in work now to develop the emotional resilience we’ll need to face them head-on and recover from them afterwards.

What are the beasts in “Beasts of the Southern Wild?”

Resilience is not so uncommon. We humans are a resilient bunch, and we’ve so far done a pretty good job of recovering from everything history has thrown our way. Take, for example, the Black Death pandemic in Europe during the Middle Ages.

In just four years, the Black Death killed about 25 million people, nearly a third of Europe’s population in the 14th century. Even before the Black Death, a 6th-century plague pandemic called the Plague of Justinian killed nearly half of Europe’s population. During this plague outbreak, nearly 10,000 people died every day in Constantinople. Yet somehow, Europe made it through plague outbreaks like these, and the period of European history between about 900 and 1300 was “…one of the longest periods of sustained growth in human history,” according to The Great Courses Daily.

And this is only one example of humanity’s ability to bounce back from major setbacks. We’ve been doing this ever since we started walking upright. In fact, we nearly went extinct in the year 70,000 B.C. after the eruption of the supervolcano Toba. I could keep listing examples, but the bottom line is this: we are hard to kill. This fact served as one of the main points of inspiration for the aurochs in Beasts of the Southern Wild.

Director Benh Zeitlin said in an interview with Pop Omnivore that his idea to use aurochs came from cave paintings he’d seen in France of cavemen fighting them off. Zeitlin said:

“The young girl in the film, Hushpuppy, sees herself as the last of her kind, on the verge of extinction. ‘How are people going to look back on my civilization?’ she wonders. And she sees herself as being in the same position as cavemen: We look back on them and understand them by their paintings. So it’s that parallel that inspired us to use the aurochs. What Hushpuppy sees as coming to destroy her is literally what a caveman painted.”

If you’re looking for a metaphor to represent the beasts we face today in the climate crisis, I can’t think of a better one than aurochs. Aurochs weren’t just made up for the movie—they were once real animals until they went extinct about 500 years ago. Unlike the porcine animals in Beasts of the Southern Wild, real-life aurochs were more like extremely aggressive bulls. Hushpuppy’s world is about to end because fossils come back to life. Sound familiar?

I suppose you could interpret this in a number of ways, but to me, aurochs have to represent fossil fuels. And just like Hushpuppy stood up to the aurochs to save her home, we must stand up to the fossil fuel industry if we want to survive. Life and death are two sides of the same coin, but in the case of drilling for oil, it’s better that some things remain dead. Hushpuppy teaches us that we can stand up to such agents of chaos. And maybe, if our convictions are strong enough, we can win.

[music: “Cold Descent” by Forrest Brown]

That’s it for our discussion of Beasts of the Southern Wild and climate change. Be sure to hit subscribe if you enjoyed today’s show, and leave us a nice review on Apple Podcasts if you feel so inclined. Doing so will help us reach more listeners who could benefit from our message.

Visit our website at storiesforearth.com for transcripts of every episode as well as additional content, and become a patron at patreon.com/storiesforearth if you want to support further production of the show. Until next time, I’m Forrest Brown. Thanks for listening.

Recommendations

Article: “Louisiana’s Disappearing Coast“

Author: Elizabeth Kolbert

Film: Okja

Director: Bong Joon Ho

Film: Glory at Sea

Director: Benh Zeitlin

Book: Chesapeake Requiem: A Year with the Watermen of Vanishing Tangier Island by Earl Swift

→ Buy USED on Better World Books from $4.66 (affiliate)

→ Buy NEW on Bookshop from $16.55 (affiliate)

→ Find at your local library