Stories for Earth relies on contributions from our listeners and readers to produce high quality, in-depth content. If you buy something using the links on our website, we may earn a small commission, at no extra cost to you. For more information, see our Affiliate Disclosure.

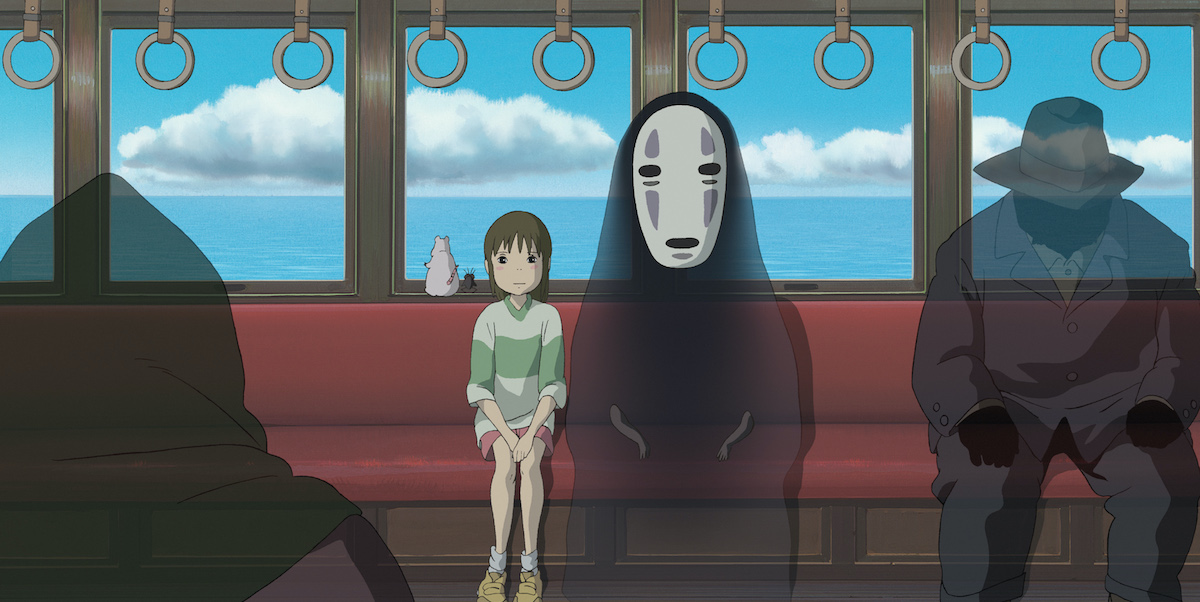

Spirited Away from Hayao Miyazaki is a Japanese animated fairy tale film released in 2001. The movie tells the story of Chihiro, a young girl on a mission to rescue her family from the evil witch Yubaba, who turned them into pigs. Widely considered to be a coming of age story about the importance of staying true to yourself, Spirited Away also incorporates many environmental themes through characters like the Stink Spirit, Haku, and No-Face.

Never miss an episode

Subscribe wherever you enjoy podcasts:

Overview

Spirited Away is one of Japanese filmmaker Hayao Miyazaki’s most-loved films. Originally released in Japan in 2001 by Miyazaki’s Studio Ghibli, Walt Disney Studios brought it to the United States in 2002. This is one of the most financially successful films in Japanese film history, and in 2017, The New York Times named it the second-best film from the 21st century so far. There are many different ways of interpreting this film, but for this episode, we take a look at the film’s environmental themes. We explore the meaning of various characters and look at what they can teach us about fighting climate change.

→ Buy the DVD on Bookshop from $19.96 (affiliate)

Jump to

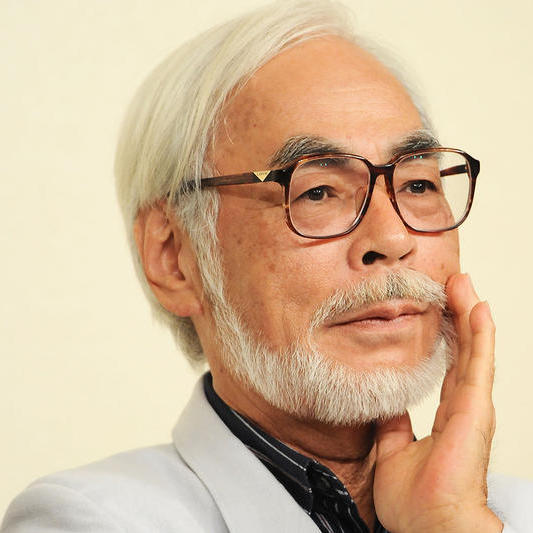

About the creator

Hayao Miyazaki is a Japanese animation director. He is widely recognized as one of the greatest living animated filmmakers in the world. Born in Tokyo in 1941, Miyazaki is famous for classic films such as Spirited Away, My Neighbor Totoro, and Princess Mononoke. Though he retired in 2017, he is reportedly working on a new movie for his production studio Studio Ghibli.

Transcript

Hello. I’m Forrest Brown, and you’re listening to Stories for Earth.

[music: “Cold Descent” by Forrest Brown]

Welcome to Stories for Earth, a climate change podcast about stories that can teach us strength and resilience in the era of the climate crisis. Today we’ll be talking about Hayao Miyazaki’s classic film, Spirited Away. But first, we have some basic housekeeping to take care of.

Two things: first, we have a website at storiesforearth.com. There you can find transcripts of the show, articles about the stories we discuss, and recommendations for further reading, among other content. We’re also on Instagram, Twitter, and YouTube if you want to follow us on social media.

The second thing is Patreon. We want to provide this show for free, and you can help us do that by supporting us through our Patreon. To make a recurring, monthly donation to Stories for Earth, go to patreon.com/storiesforearth, or visit our website and click “Support us on Patreon” from the navigation menu.

Now, without any further ado, let’s get on to today’s episode. And don’t worry, if you haven’t seen Spirited Away before, I’ll fill you in on all the details so you can still get something meaningful from our discussion.

“Spirited Away” plot summary

Spirited Away is the story of a young girl named Chihiro who gets stranded in a spirit world after she and her parents wander into an abandoned Japanese amusement park. They’re in the process of moving to a new town, and they find the amusement park after Chihiro’s dad tries to take a shortcut on a dirt road through the woods.

Chihiro’s time in the spirit world begins with her parents eating enchanted food, which turns them into pigs. To turn her parents back into humans and to escape from the Spirit World, Chihiro has to get a job at the local bathhouse, which is run by a witch named Yubaba.

If you’ve ever seen a movie from Hayao Miyazaki, you’ll instantly recognize this as a signature Miyazaki story. Miyazaki’s movies usually feature young—often female—protagonists who have to overcome some sort of great evil to save the day, and there are usually many fantastical or fairy-tale like elements involved.

For example, in another one of Miyazaki’s films called Howl’s Moving Castle, a young girl named Sophie is transformed into an old woman by an evil witch, and the only way for Sophie to break the curse is to work for a wizard named Howl in his enchanted castle.

Along the way, Sophie meets a scarecrow who turns out to be a cursed prince, and she winds up having to keep two kingdoms from going to war on behalf of Howl. Sophie succeeds in turning back into her younger self, and she breaks the prince’s curse, restoring him to his human form and averting the war.

Howl’s Moving Castle is heavy on a theme Miyazaki is known for playing with in most of his films: pacifism. This doesn’t come as much of a shock when you look at his personal life. He was born in Tokyo in 1941 and lived through World War II when Japan was part of the Axis Powers along with Nazi Germany and Fascist Italy. Miyazaki experienced some horrors of war firsthand, like firebombings, and he of course witnessed the aftermath of America dropping atomic bombs on Hiroshima and Nagasaki. These bombings killed between 129,000 and 226,000 people, most of whom were civilians.

Against this apocalyptic backdrop, I can’t blame Miyazaki for being a pacifist and for promoting pacifism. But in addition to the human suffering war causes, Miyazaki also realized its capacity for tremendous environmental destruction, especially from pollution and nuclear weapons.

Spirited Away doesn’t depict a nuclear war, but it does focus heavily on the pollution aspect, which Miyazaki sees as an adverse result of consumerist greed and industrialization.

We see this the most in the movie through three different characters. The first is called the Stink Spirit.

The Stink Spirit

The Stink Spirit appears after Chihiro first starts working at the bathhouse. Also, it’s important to note that after getting a job at the bathhouse, the witch who runs it, Yubaba, gives Chihiro a new name: Sen. I’ll talk about the significance of this in a little bit, but for now, just keep in mind that when I say “Sen,” I’m talking about Chihiro, our protagonist.

The Stink Spirit looks like a giant sludge monster, and based off the way the characters in the movie react to its presence, you can tell it really stinks. The other bathhouse workers try to keep it from entering, but it trudges forward, insistent on getting a bath.

Naturally, no one wants to take care of the Stink Spirit, so Yubaba makes Chihiro do it as a sort of hazing or initiation task. Chihiro, never one to be stopped, carries out the work of bathing the Stink Spirit dutifully. In fact, she works so hard to get it clean that she accidentally falls in the bath with it.

And it’s in this scene, while Chihiro is struggling to get out of the bath, that she feels something pointy coming out of the Stink Spirit’s side, like a thorn. Once she gets back out, Chihiro enlists the help of the bathhouse staff to pull this thing out of the Stink Spirit. But when they’re finally able to yank it out, Chihiro realizes the thorn is really a bicycle handlebar, and pulling it out releases a deluge of trash and pollutants.

With the pollution gone, all the sludge surrounding the Stink Spirit dissolves to reveal a River Spirit. People throwing pollution into the river made it a Stink Spirit, but Chihiro saved it, and it thanks her by giving her a ball of medicine before leaving.

Shintoism in “Spirited Away”

In some ways, this story really happened. Miyazaki got the idea after working on a river cleanup when he pulled a bicycle from the river.

Hearing this made an impression on me because it sounds like animism, which is the belief that everything—including plants, animals, so-called “inanimate” objects, and natural phenomena—have souls. And of course, animism is central to the ancient Japanese religion Shinto, or Shintoism.

Practitioners of Shintoism, usually called Shintoists, believe in supernatural beings called kami. Kami inhabit the landscape, and they can either be benevolent or malevolent towards humans, depending on whether or not humans honor them properly. In Japan, there are shrines to kami all over the place, and you can also see them in the opening scenes of Spirited Away.

In an interview with Robert Epstein from The Independent in 2010, Miyazaki said, “I do not believe in Shinto…but I do respect it, and I feel that the animism of Shinto is rooted deep within me.”

But Spirited Away pays homage to another important aspect of Shintoism as well: the purifying power of water. In Shintoism, cleanliness is very important. It’s just like that old saying in English, “Cleanliness is next to godliness.” Yubaba’s bathhouse, then, is a place where spirits can come to be purified. It just so happens that a number of these spirits turn out to be nature spirits, like rivers.

The importance of Haku

There’s another important river spirit we meet in Spirited Away, though we don’t realize what it is at first. Spoiler alert if you haven’t seen the movie, but I’m talking about Haku, a young man who helps Chihiro when she realizes she’s stranded in the spirit world. Haku is the one who tells Chihiro she must get a job working at Yubaba’s bathhouse, and he also teaches her the importance of remembering her name after Yubaba gives her a new one, warning her that if she forgets it, she’ll be stuck in the spirit world forever.

Haku, it turns out, has firsthand experience with this. He’s really the spirit of the Kohaku River, but he can’t escape the spirit world because he’s forgotten his name. Near the end of the movie, Chihiro realizes she met Haku several years before when he saved her from drowning in the Kohaku River. Now, Chihiro says, the river has been filled up to make way for apartment buildings.

Harnessing the power of rivers

Japan is a beautiful country full of mountains, lakes, and streams, though its rivers are known for being shallow and short due to the country’s mountainous topography. Rivers hold historical significance for supplying drinking water and for creating alluvial plains, which are perfect environments for growing rice. But in modern times, Japan builds a lot of hydroelectric dams on rivers to generate power.

This is common practice all over the world. Where I grew up in the United States, I lived near the Buford Dam just north of Atlanta, Georgia. And while it doesn’t generate electricity, it does hold back water from the Chattahoochee River to create Lake Lanier, a giant reservoir that supplies drinking water to Metro Atlanta. Out West, we have the famous Hoover Dam, which straddles the Nevada-Arizona border on the Colorado River.

This giant hydroelectric dam supplies power to nearly 8 million people across Southern California, Southern Nevada, and Arizona. But even it pales in comparison to a hydroelectric dam in China called the Three Gorges Dam, which is located in the Yangtze River Basin. The Three Gorges Dam cost $31 billion to build, and it produces roughly eight times the electricity of the Hoover Dam.

Oh, and it also holds the unique distinction of being both the world’s biggest dam and the world’s biggest power station. The reservoir it created is bigger than Lake Superior in the American Midwest. It’s extremely difficult to overstate the sheer enormity of this dam.

As you can imagine, the Three Gorges Dam didn’t come without resistance from scientists and environmentalists who were concerned about the potentially devastating effects the project could have on the local environment. Not to mention the effects it would have on the 31 million or so people who lived in the area.

According to a Scientific American article from 2008, construction of the dam required about 1.2 million people scattered across two cities and 116 towns to relocate, and scientists were concerned that building the dam would cause an increase of landslides and waterborne diseases, which would further impact the people who didn’t have to relocate.

These fears turned out to be true after construction of the dam was complete. The Chinese state-owned China Yangtze Three Gorges Development Corporation began raising the water level in 2003, triggering a landslide that created waves big enough to kill 14 people. Years later, increased pressure on the land from raising and lowering the water level led to a landslide that swallowed a bus, killing 30 people.

At one point in 2007, residents of a nearby village watched as a giant crack in the earth spread 655 feet wide just behind their homes. The crack was so huge that concerns for public safety led Chinese officials to evacuate the town, forcing villagers to camp out in a mountain tunnel for three months.

The worst part of all of this is that landslides were only part of the problem. Building the Three Gorges Dam also led to decreased rainfall and water shortages in other cities and towns, and building the reservoir caused great harm to endangered species of plants and animals in the extremely biodiverse areas surrounding the Yangtze River.

But fixing these problems won’t be as simple as demolishing the dam and trying to put everything back the way it was before. China spent tens of billions of US dollars building this dam, and tearing it down would surely be just as destructive as building it in the first place. Plus, the Three Gorges Dam was, at the time of its construction, an important piece in China’s plan to reduce its greenhouse gas emissions.

China relies heavily on coal for electricity generation, and the Three Gorges Dam was a huge effort to source more electricity from hydro, which is a renewable energy source. Cutting reliance on coal is important, but I think—and I’m sure you would agree—that China didn’t go about this in the best way with the Three Gorges Dam project.

No Face and self-destructive greed

We’ve already talked about the environmental implications of the Stink Spirit and Haku, but I can’t help but thinking of another character here. And honestly, what would a discussion of Spirited Away be without mentioning one of its most iconic characters: No Face.

No Face comes to the bathhouse after the Stink Spirit leaves. It’s been raining for a long time, and Chihiro sees him outside in the garden. She feels sorry for him, so she lets him in.

Now, just after No Face enters the bathhouse, Chihiro has to attend to a sick Haku, so she doesn’t really get to know anything about No Face. But No Face almost immediately starts wreaking havoc, offering the bathhouse staff huge amounts of gold nuggets for all the food they can bring him. In the process, he actually eats several staff members.

The bathhouse staff remain undeterred by this, and they keep bringing him food to get more gold. When Chihiro finally returns and tames No Face, all the gold turns into mud. The bathhouse staff were risking getting eaten alive for a kind of fool’s gold.

I thought of this when reading about the Three Gorges Dam because the No Face incident seems like the perfect metaphor for what happened in China. Some people see an opportunity for wealth and power, and even though it will cost others their lives, they decide to keep building, keep bringing more resources to feed the monster. We aren’t quite there yet, but what will happen when all the gold we get from projects like the Three Gorges Dam turn to mud, so to speak? Will it have been worth it?

Chihiro’s relationship with Haku

Before we wrap up our discussion, I want to go back to Chihiro’s relationship with Haku. Yes, Chihiro winds up saving Haku by remembering his name, but Haku actually helped Chihiro remember her name first.

In the beginning of the movie, just after Chihiro gets the bathhouse job and Yubaba gives her her new same, Sen, Haku reminds her of her real name and warns her never to forget it. Frightened, Chihiro confesses she had already forgotten her real name and thanks Haku for reminding her.

This is significant because of who Haku really is, the spirit of the Kohaku River. And whether you believe in kami or stink spirits or animism in general, there’s no denying that what we do to the natural world has consequences, and these consequences can be dire. Water is precious for its life-sustaining and purifying qualities, but when we pollute it, it can become a source of disease and destruction.

We see this with the Stink Spirit and No Face, but Haku shows us how water and nature in general give back to us. Chihiro only knows Haku’s real name because he saved her from drowning as a young girl. And Chihiro may have even forgotten her name if Haku hadn’t reminded her.

This is what the natural world does for us. It provides us with the resources we need to live, and it even helps us remember who we really are. As humans, it’s easy to forget our identities amid our grand aspirations and innovative new ideas, but nature brings us back down to earth, so to speak, reminding us of our place in the universe. In a way, it helps us to remember what makes us human to begin with.

In terms of climate change, Chihiro’s relationship with Haku shows us that if we care enough and try hard enough, we can save the things we love. We’ll need all the help we can get along the way, sure, but sometimes saving someone or something starts with remembering their name—who they are and who they’re supposed to be.

[music: “Cold Descent” by Forrest Brown]

That’s it for our discussion of Spirited Away. If you like what you heard today and want to learn more, visit our website at storiesforearth.com for more episodes, articles, and recommendations for further reading.

If you got real value from today’s show, please consider supporting us through Patreon so we can keep doing it. You can find us at patreon.com/storiesforearth.

Until next time, I’m Forrest Brown. Thanks for listening.

Recommendations

Film: Nausicaa Of The Valley Of The Wind from Hayao Miyazaki

Film: Princess Mononoke from Hayao Miyazaki

→ Buy the Blu Ray on Bookshop from $29.95 (affiliate)

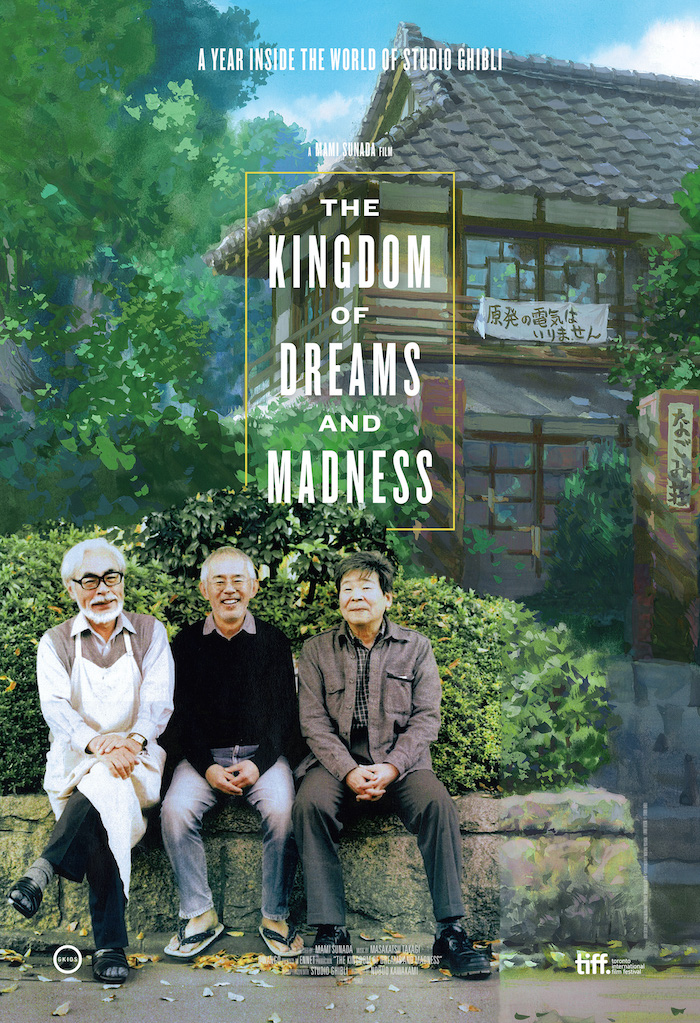

Film: The Kingdom of Dreams and Madness from Mami Sunada

Article: “Animating child activism: Environmentalism and class politics in Ghibli’s Princess Mononoke (1997) and Fox’s Fern Gully (1992)” by Michelle J. Smith and Elizabeth Parsons

Essay: “The Ecological Imagination of Hayao Miyazaki: A Retrospective on Four Fantastical Worlds” by Isaac Yuen in Orion Magazine